Celts and Vikings - Scandinavian Influences on the Celtic Nations

In the Celtic world, there are many Scandinavian influences. Within Scotland, Ireland and Isle of Man, the Vikings influences were mainly Norwegian. The Norwegians established significant settlements and then Kingdoms here. In Wales, there were recorded Viking raids and some evidence of small settlements. In Cornwall, strategic alliances were formed with Danish Vikings in order to defend Cornish lands from Anglo-Saxon incursion. Brittany experienced significant Viking raids and occupations. However, at times, strategic alliances were made, which can be viewed in the context of Breton resistance to Frankish expansionism and the complicated power struggle that existed during that period.

The Vikings in Scotland and Isle of Man

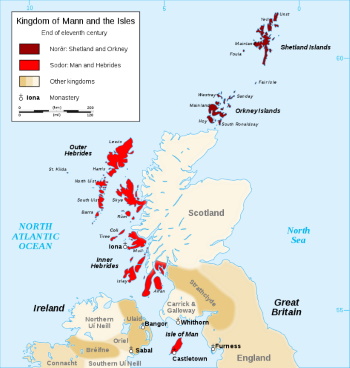

The Viking interventions began in the 8th century AD. The Islands of Scotland and the Isle of Man formed the Northern and Southern Isles. The Northern Isles of Shetland and Orkney were known to the Norse as Norðreyjar. The Southern Isles forming the Kingdom of Mann and the Isles (sometimes known as The Kingdom of the Isles) consisting of the Hebrides, the islands in the Firth of Clyde and the Isle of Man were known as Suðreyjar.

The Southern Isles (Suðreyjar) experienced changes in power and control during the 9th to 13th centuries AD. There were significant periods of independent rule and times when there were overlords in Norway, Scotland, Ireland and Orkney. Perhaps the most famous Norse legacy is the Isle of Man’s Parliament, Tynwald. The name is derived from the Norse ‘Thingvalla’ which means ‘Assembly Place’. The Manx have retained the system of government introduced by the Norse. The Manx Parliament of Tynwald is the oldest continuous parliament in the world and there were other such assembly sites in Scandinavia.

At the time of the Norse Kings the Isle of Man was the centre of the significant Kingdom of Mann and the Isles. These Southern Isles (Suðreyjar) were ruled by a Tynwald which had 32 members, with 16 from the Isle of Man and 16 from the Isles of Skye, Mull and Lewis. In the twelfth century Argyll took control of Mull and Islay and with the loss of their eight assembly members Tynwald was reduced in size from 32 to 24.

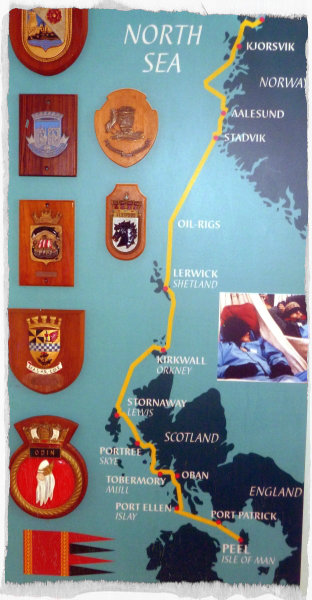

A remarkable acknowledgement of the Viking historical contribution to the Northern and Southern Isles took place many centuries later. On Sunday May 27th 1979, as part of the ceremonies celebrating the Millennium of Tynwald, a mixed Manx and Norwegian crew set sail from Trondheim in Norway on a voyage to Purt ny h-Inshey (Peel) in the Isle of Man. The journey was undertaken in a two thirds replica Viking boat called Odin’s Raven. The vessel was based on the Gokstad Ship built in 850 AD.

The boat was navigated along the Norwegian coast south from Trondheim calling at Kjorsvik, Aalesund and Stadvik. The next stage of the route was across the North Sea to Scotland calling at Lerwick in Shetland and Kirkwall in Orkney. Then it followed the western isles of Scotland to Stornaway in Lewis, Portree in Skye, Tobermory in Mull, Oban, Port Ellen in Islay, Portpatrick on the west coast of Dumfries and Galloway before finally reaching its destination in Purt ny h-Inshey (Peel), Isle of Man.

The last king of Mann was Magnús Óláfsson, descended from a long line of Norse-Gaelic Kings who ruled the Isle of Man and parts of the Hebrides. Both King Alexander II of Scotland in the 1240’s and then later his son King Alexander III tried to purchase, then when this failed attempted military force to gain the Isles. King Hákon Hákonarson of Norway (1204 to 1263) sought to defend the lands against the expanding power of Scotland. However after his death in 1263 Scottish incursions increased. According to the Chronicle of Mann, King Magnús Óláfsson then died in 1265 at Rushen Castle in the Isle of Man and was buried at nearby Rushen Abbey. A year later, after the Treaty of Perth, Mann and the Hebrides were ceded to the Kingdom of Scotland.

The Treaty of Perth on 2nd July 1266 was agreed in order to end conflict between Norway and Scotland. Under the treaty Scotland was given sovereignty of the Hebrides and Isle of Man upon agreement of payment to Norway. At the same time Scotland recognised Norwegian sovereignty over Shetland and Orkney.

The Northern Isles (Norðreyjar) were subject to Viking invasions from the 8th Century and became a Viking stronghold. The Norwegian King Harald Hårfagre took control of the Islands in 875 AD and they became an earldom. They were ruled as a province of Norway and under the Jarl (Earl) during the Earldom of Orkney (rule also extended into parts of Caithness and Sutherland). King Christian I pledged the Islands as security for the dowry of his daughter Margaret of Norway who became Queen Margaret of Scotland (1469 to 1486) upon her marriage to James III of Scotland. The dowry not being paid the islands became part of the Kingdom of Scotland in 1471. Norwegian law was not abolished in Shetland until 1611 and the Norse based language of Norn continued in common use for over two centuries after that.

The Norse influences on the life and peoples of the islands of Orkney and Shetland remain clear today. In the names of people, place names, customs and archaeology. Examples include the festival of Up Helly Aa which is held in Shetland in January every year culminating in the burning of a Viking galley. In 1991 on the beach at Scar on the Orkney island of Sanday a Viking ship burial was excavated. Within it were human remains and grave goods. The boat has been dated to between 875 and 950 AD.

The settlement of Orkney and Shetland did not start with Viking migration. Throughout the islands there is evidence of inhabitants from at least the Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age through to the Pictish period. The people of the Pictish period were the descendants of the earlier indigenous population of pre-history, as were the Gaels. Little is known of the people of the Pictish period, other than that they inhabited northern Scotland. Probably they were groups of people with different traditions who may have been forced into greater unity in response to external threats.

There is no clear evidence of what happened to the Picts of the Northern Isles after Viking settlement. There have been suggestions that they deserted the islands, or were destroyed by the new arrivals. However, there is some evidence that they intermarried and were assimilated into Norðreyjar. Pictish tools have been found in the excavations of Viking settlements. This is the pattern in the Southern Isles (Suðreyjar), where there is clear evidence of assimilation; indeed the Vikings were integrated by the Gaelic peoples and eventually spoke their language. However, it needs to be remembered that in the Northern Isles of Orkney and Shetland the passing from Norwegian control to Scotland did not take place until the fifteenth century. The spoken language was Norn, a form of Norse.

The Vikings in Ireland

795 AD saw the first recorded raid on Ireland with the attack and plunder of the church in Lambeg Island. Iona was also attacked in that year and two further raids within a decade led the religious community to leave the island and move to Kells in Meath. Over this period there was an increase in Viking raids from Norway along the west coast of Scotland and then off the Irish coast. The Vikings were skilled navigators using their technologically advanced long ships to ply the stormy seas off northwest Europe. At the same time their sleek boats could enter into narrow rivers and make landing on beaches.

These raids later developed into more serious attempts at colonisation after 837 AD, with efforts to establish permanent strongholds. Dublin, present day Eire’s capital city, was founded by the Vikings after they established such a base at the mouth of the Liffey. It was from here that they mounted further incursions into Ireland. At this time Ireland was made up of a number of kingdoms. In the Ireland of the 9th century this made an organised defence of the island of Ireland difficult to achieve. The Norse state that developed in Dublin became a significant factor in Irish internal life, with alliances being formed with some Irish leaders. At the same time Dublin became a significant international trading centre.

The year 914 AD saw the Vikings sailing into Waterford and establishing a base from where their reach could extend into Munster. Later bases included what subsequently became known as Limerick following the Viking invasion into the Shannon estuary. The city of Cork in Munster, although starting out as a sixth century monastic community, developed from the Viking settlement there after 914 AD. The town of Wexford also has its origins in the settlement of Veisafjǫrðr from where it derives its name and remained a Viking town for some 300 hundred years from about 800 AD. Waterford’s name comes from the Old Norse name for the settlement, Vedrarfjiordr, which was established in the late ninth century. There are other such examples of place names in Ireland that point to Viking involvement.

A significant event in ending the Viking wars in Ireland is thought to be the Battle of Clontarf, which reached its climax on 3rd April 1014. At that time Brian Boru had grown to be High King of Ireland as he sought to make other kings pay allegiance to him. However, Mael Morda, King of Leinster formed a pact with the Viking King of Dublin to resist Brian Boru. Although victorious, Brian was killed at Clontarf. This was not though the end of the Vikings in Ireland. Even before the emergence of Brian Boru the Vikings had settled, intermarried and their settlements had formed part of Irish political life. This ran alongside all of the associated battles at times with some Irish rulers and then alliances with others.

Vikings in Wales, Cornwall and Brittany

Wales

Despite many raids (the first recorded was in 852 AD) there was no significant Viking colonisation in Wales, although settlements existed in the south of the country and in Anglesey. Places such as Swansea (derived from the Norse name Sweyns Ey), Worms Head, Skokholm and Skomer are examples of these small settlements. The island of Anglesey in the northwest of Wales was subject to attacks and was clearly well known to the Vikings. The name Anglesey (Onglesey) is of Norse derivation along with other place names on the Island. It is also known that Vikings arrived there after being driven out of Dublin in 903 AD. Anglesey is also a just hours sailing distance from the Viking stronghold of the Isle of Man.

Overall the powerful Welsh kings, despite their internal disputes, prevented the establishment of Viking states or control. Rhodri ap Merfyn (Rhodri Mawr - 844 to 878) the ruler of Gwynedd was one such leader of opposition to early Viking incursion and in 855 killed Gorm the Danish leader. The situation over the period of Viking expansion was not always one of hostility between Welsh and Vikings. At times alliances were formed in opposition to the Anglo Saxons.

Cornwall

Cornwall was also able to defend itself against any major Viking incursion. Indeed during the 8th century AD Cornish-Viking alliances were made in efforts against expansions by the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Wessex. In about 870 AD at the Battle of Hehil the Anglo-Saxons were defeated and this helped delay further expansion into Cornish lands. This was helped by subsequent continued Danish Viking raids on the Saxons.

Brittany

Brittany's relationship with the Vikings needs to be seen in the context of its resistance to Frankish rule and the general political power struggles that were taking place between the ninth and eleventh centuries. There were various groups of Scandinavians operating at the time, often collectively known as Vikings, but with different objectives. At times there were brutal Viking attacks on Brittany. At other times the Viking wars with the Franks gave an opportunity for Breton consolidation of territories. On occasion alliances were made with the Danish Vikings to contain Frankish expansionism. Following the defeat of the Frankish kingdoms at the Battle of Brissarthe in 865 AD the Franks had to accept Brittany’s independence.

The situation was complicated by internal Viking divisions with the Bretons siding with one group of Vikings against another in order to defend themselves and their territory. However, the eventual strengthening of the Franks ability to defend themselves against attack and their alliances with the Vikings resulted in major Viking incursion into Brittany. The last recorded raid on Brittany was in 1014, with the attack on Dol by a Viking fleet.

Viking Assimilation into the Celtic Lands

In Ireland, rather than conquering, the Vikings ended up being assimilated by the Irish. The same was true in the Scottish Isles and Isle of Man. Place names reveal their influences, as do family names. Irish Family names derived from Old Norse include, Mc Sorley, Lamont, Mc Keever, Mac Manus, Mac Caifrey, Reynolds, Kitterick, Kettle . In the Isle of Man, surnames of Norse origin include Corkill, Crennell, Cottier, Cormode, and Kinvig amongst others. In Scotland there are also many such examples which include those of the Norse-Gaelic Clan Donald including the various branches of the MacDonald’s, MacAlister and MacDonell.

The MacDonalds traditional support of Norway against the Scots was only broken after the Battle of Largs in 1263 with the defeat of King Haarkon.and the subsequent relinquishing of the islands to the Scottish crown some years later. Another of the Norse-Gaelic clans was the Clan MacLeod where the name is thought to derive from the Old Norse name Ljótr. The family claim a descent to the Kings of Mann and the shield of the chief of the Clan MacLeod incorporates the ‘three legs of mann’.

The legacy of the Vikings can be seen throughout the Gaelic world. A remarkable surviving physical example of this is the Manx carved stone crosses on which Norse and Gaelic names are carved. Earlier Celtic Crosses on the Island carry Celtic designs and the early Celtic script known as Ogham. Later Norse sculptors decorated their crosses and incorporated tales from pagan mythology. Amongst the many such examples on the Isle of Man are the four carved Norse stones known as the ‘Sigurd Stones’. They depict scenes from the heroic Norse legend of Sigurd Fafnir's Bane. On a side of one of the stones in the village of Andreas the hero Sigurd is shown roasting Fafnir the dragon's heart and sucking his fingers. The head of a bird and his horse can be seen in the background. The other side of the stone depicts a subsequent part of the tale. It shows the figure of Gunnar, who is Sigurd's foster brother, being bitten by serpents and then cast into a pit of vipers.

In Orkney place names are now practically all Norse in origin and number many thousand that are derivatives or corruptions of original Old Norse names. These old Norwegian words are found mingled with some words of Celtic origin and occasional Scottish ones introduced later. Geneticist Professor David Goldstein from University College London led a fifteen month genetic study which formed the basis of a five part BBC documentary that looked at the Viking heritage remaining in the areas of the Northern (Norðreyjar) and Southern Isles (Suðreyjar). High concentrations of Norwegian genetic heritage were found.

An interesting additional factor in the story of the Celts and Vikings is that of the Papar. They were early Gaelic monks whose existence is proven by archaeology and also recorded in historical Icelandic sources, the earliest of which is the Íslendingabók (The Book of Icelanders) written between 1122 and 1133. The later Landnámabók (Icelandic book of Settlements) points to how when the Norwegians started settling Iceland in 874 AD they found these monks already there. There are examples of the Papar influence in the Northern Isles as seen by the island names of Papa Westray and Papa Stronsay in Orkney and the districts in Shetland with the name Paplay or Papplay. In islands of the Outer Hebrides there are those baring the name in Gaelic of Pabaigh.

Further reading...

Information on the Vikings in the Celtic World

This comes from a variety of sources. The archaeological evidence includes a number of sites on the Isle of Man, Orkney and Shetland, Ireland and Wales. There have been remarkable discoveries such as the Lewis Chessmen, thought to date from the 12th century and found in 1831 on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Viking ship burials have been uncovered and artefacts found from sites in the Northern Isles and the Southern Isles. There are written records from monasteries and later sources as listed below:

- Orkneyinga saga, a Norse saga, thought to date to about 1230 AD and written by an Icelandic scholar.

- Flateyjarbók written in Iceland between the years of about 1387 to 1394. Also known as the Flatey Book it also contains a version of the Orkneyinga saga.

- Chronicles of Mann (Chronicles of the Kings of Mann and the Isles) thought to have been written in about 1261 at Rushen Abbey and recording events from previous centuries and handed down in oral tradition.

- The Irish Annals of Ulster that give the span 431 AD to 1540 AD. Compiled in the late 15th century using sources from monastic institutions and oral history.

- Annals of Tigernach spanning periods from 488 to 1178. Ascribed to Tigernach hua Braein Abbott of Clonmacnois, Ireland who died in 1088. Covers events 322 BC to 360 AD, 489 AD to 766 AD, 975 AD to 1088.

Museums

To get clear a perspective from exhibitions, reconstructions and various artefacts then visiting various museums such as listed below is highly recommended:

- The Shetland Museum and Archives. The new museum in Hay’s Dock, Lerwick, Shetland, Scotland was opened by Queen Sonja of Norway 31 May 2007.

- The Orkney Museum, Tankerness House, Broadstreet, Kirkwall, Orkney, Scotland.

- Dublinia (Viking and Medieval Dublin)

- Thie Tashtee Vannin (Manx Museum), Douglas, Isle of Man

- Thie Vanannan (House of Manannan), Quay Side, Purt ny h-Inshey (Peel), Isle of Man

- Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum of Wales

- Pan-Celtic

- English

- Log in to post comments