Celtic Harvest Festival of Lughnasa

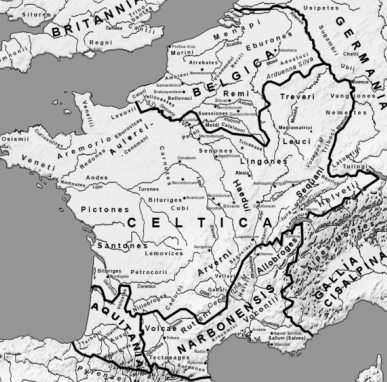

The Celtic harvest festival of Lughnasa, traditionally celebrated on the first of August, is the fourth and last of the Feast days of the Celtic year. Although these four feast days are usually referred to as festivals of the pre-Christian Irish Celts, there is evidence that each of the four feast days have more ancient roots and that they were at one time celebrated throughout the Celtic world.

The connection between the four feast days and ancient Celtic religious practices is illustrated by the famed Coligny Calendar. The Coligny calendar records the important dates in the Celtic year. This artifact, unearthed in France in the late 1897, and which dates from about 200 AD, was created by the Celts of Roman Gaul. There is speculation that the calendar was created by Gaulish Druids to preserve the Celtic religious calendar at a time when Gaulish Celtic culture began to be submerged into the Roman way of life, three centuries after the rape and subjugation of Celtic Gaul by Gaius Julius Caesar.

It is argued that all four of what we now refer to as the Feast days of the Celtic year are rooted in ancient Pan-Celtic religious practices from a time when Celtic culture spanned Europe from Donegal to the Black Sea.

The esteemed Celtic scholar James MacKillop, in his 2005 “Myths and Legends of the Celts”, comments on the evidence supplied by the Coligny calendar on the link between the four feast days of pre-Christian Ireland and the ancient continental Celts. " Such clear links between the continental and insular Celts (Irish) are rare. This endorsement from the Coligny Calendar of Irish antiquity’s inheritance from earlier antecedents, added to the extensive texts and critical prestige of early Irish tradition, has meant that commentators prefer the classical Irish names for four of the calendar feasts. They are Samhain (November 1st), Imbolg (February 1st), Beltane (May 1st) and Lughnasa (August 1st). The four days are also known by other names in the other Celtic countries."

Samhain (Halloween)

This is the pre-eminent Celtic feast day as it has survived, flourished and conquered the modern psyche. The ancient Celtic holiday of Samhain, universally known to us as Halloween, was the start of the Celtic New Year. This is when the Druids lit bonfires marking a period of great danger to mortal souls. The bonfires were a warning that the laws of nature were suspended and the barriers between the natural order of things and the Celtic Underworld were dissolved, when the Underworld became visible to the living and the Fairies and the Dead would come forth. Ordinary folk were highly vulnerable to being kidnapped by Fairies and taken to the Underworld at this time and it was ill advised to go near the many "Fairie Mounds" which are said to have dotted the Celtic countryside. Halloween costumes may have originated from a tactic employed to ward off the unpleasant spirits unleashed at Samhain who, as some legends have it, would look for those still living who were in mortal life the adversaries of dead who now returned on this night. Jenny Butler, Folklorist at University College Cork's Folklore and Ethnology Departments states in an interview published by the Archeological Institute of America: "One of the theories of guising and dressing as ghosts may be the notion that the dead are returning on this night and the change of appearance may protect the human from being recognized by the returning spirits of the dead". One suspects that this did not fool the Fairies. Something for us all to keep in mind this Halloween is that if you are not staying indoors, you better have a convincing costume.

Imbolg

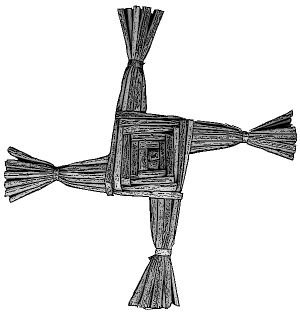

The second feast day of the Celtic year, Imbolg, celebrated on February 1st was originally the feast day of the Celtic Goddess Brigid. Brigid was an immensely important deity in the Celtic pantheon who was absorbed in to the Feast day of the Christian Saint of the same name and is celebrated on the same day. Imbolg marks the advent of the traditional agricultural year and the start of the lactation of domesticated sheep, an important annual milestone to the pastoral Celt. In his work "Dictionary of Celtic Mythology", Peter Beresford Ellis describes Brigid as a powerful goddess who would manifest herself in one of three ways: "...who appears as a goddess of healing, a goddess of smiths and more popularly, a goddess of fertility and poetry.” Miranda Green in her work the "Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend" states, "The name of the Celtic goddess was originally an epithet meaning "exalted one". Brigid is of especial interest because she appears to have undergone a smooth transition from Pagan Goddess to Christian Saint". Perhaps nothing typifies the successful tactics of Christian conversion more than the fate of Brigid. Brigid, daughter of the Celtic Mother Goddess Danu, who has spent the past 1600 years confined to the rigid hierarchy of the Christian liturgy. The story and fate of Brigid, as much as any other, demonstrates how expert were the Christian missionaries in weaving Celtic myth into Christian belief making it seem as if the new religion was really an extension of the existing faith in the Gods of the Celtic Pantheon.

Beltane

Beltane, the third of the Celtic Festivals, celebrated on May 1st, has survived in essentially archaic form due in part to its simplicity in that the celebrations historically included the lighting of bonfires. Remnants of the Beltane tradition have survived into modern times throughout the Six Nations and are experiencing resurgence. Beltane, celebrated on May 1st, is the third of four annual Celtic Feast Days. There is evidence that Beltane had its origins in rituals associated with the Pan-Celtic Solar God "Bel" and it is believed that the Druidical Orders historically played a central role. "This was a time when the Celts offered praise to Bel, who was not only a god of death but of life as well, for he is represented as a solar deity and he was regarded as having gained victory over the powers of darkness by bringing the people within sight of another harvest. On that day (Beltane) the fires of the household would be extinguished. At a given time the Druids would rekindle the fires from the torches lit by 'The Sacred Fires of Bel', the rays of the sun, and the new flames symbolized a fresh start for everyone" (Ellis). The Celtic Otherworld opens on Beltane, as it does on Samhain (Halloween), but unlike at Samhain the Beltane door to the Otherworld is associated with rebirth and renewal: "As with other such festivals, Beltane began at sundown on the eve of the festival day. Like Samhain in the fall, Beltane was a day when the door to the Otherworld opened sufficiently for Fairies and the dead to communicate with the living. Whereas Samhain was essentially a festival of the dead, Beltane was one for the living, when vibrant spirits were said to come forth seeking incarnation in human bodies or intercourse with the human realm" (Patricia Monaghan -Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore).

Lughnasa

The name of the last feast day of the Celtic year is based on the name of the continental Celtic god Lugos, antecedent to famed Irish deity Lugh. James MacKillop describes Lughnasa as the least known of the four feast days; “The last of the four calendar feasts, Lughnasa, may be the least perceptible in the industrial, secular society, but we know more about its ancient roots than any of the other three.” The significance of Lughnasa began to fade and the date on which the shadows of the ancient harvest festival was celebrated began to be moved to suit its connection with modern, often Christian, celebrations observed at about the same time of year. “The Christian Church did not oppose the continuation of the festival marking the beginning of the harvest…..but the different names applied to it obscured its pagan origin. As the Christian church often substituted the archangel Michael for Lugh, the festival was transformed into St. Michael’s Day or Michaelmas and moved to 29 September. Perhaps there was no way for Lughnasa to survive in a society increasingly insulated from the significance of natural processes. August has become a time for leisure activities, for holidays and vacations, not for shadowy commemorations of forgotten deities.” (MacKillop)

Note on Spelling: There are multiple spellings of Brigid, Lugh, Samhain, Imolg, Beltane and Lughnasa. We have chosen these spellings as among the most widely used and to ensure consistency in presentation.

Further reading...

Peter Beresford Ellis: "Dictionary of Celtic Mythology"

Miranda J. Green: "Dictionary of Celtic Myth & Legend"

Patricia Monaghan: "The Encyclopaedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore"

James MacKillop: "Myths & Legends of the Celts"

James MacKillop: "Dictionary of Celtic Mythology - Oxford"

Content type:

- Pan-Celtic

Language:

- English

- Log in to post comments