The Mystery of Scotland’s Flannan Isles Lighthouse

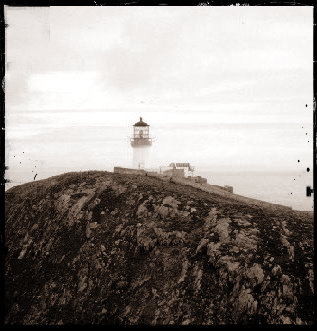

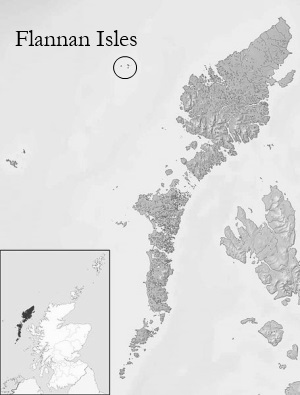

Na h-Eileanan Flannach is the Scottish Gaelic name of the small group of islands known in English as the Flannan Isles, located in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides (Na h-Eileanan Siar). Also known as the Seven Hunters they stand just over 20 miles (32 kilometres) from the Isle of Lewis (Leòdhas ). They are a bird sanctuary and at times a place of beauty. At others these remote islands bear the brunt of severe Atlantic storms, which whip the seas into frenzy and force even the hardy gulls to stay sheltered in the cliff face crags. For many years they have remained uninhabited, the last residents of any length being the lighthouse keepers, who between 1899 and its automation in 1971, kept the light burning on the highest point of the island group, Eilean Mòr.

Until the lighthouse had been built between 1895 and 1899 it is probable that Na h-Eileanan Flannach had not been inhabited permanently since the days of the Celtic Church. The Celtic Church was predominant across the Celtic speaking world in the early middle ages (5th to the 10th century). On the island of Eilean Mòr is the ruin of an old chapel dedicated to St Flannan. However, over many centuries for many of the Gaelic Hebridean community the islands have been viewed as a place of superstition and bad luck. A view that was reinforced by the tragic and mysterious events that befell the lighthouse keepers on Eilean Mòr in mid-December 1900.

It is the fate of the lighthouse keepers in 1900; just over one year after the island’s lighthouse came into operation that is the cause of much mystery and speculation. For all three keepers, Thomas Marshall, James Ducat and Donald Macarthur disappeared without trace. It was on 15th December 1900 that the ship Archtor which was sailing for Scotland from Philadelphia had reported that as they passed the islands the lighthouse was not in operation. In those days there was no radio communication between the keepers on Eilean Mòr and the shore station of Breasclete on Lewis. When the lighthouse tender Hesperus arrived on St Stephen’s Day (26th December) 1900 having been delayed due to adverse conditions, they found the lighthouse abandoned.

The first man ashore was relief keeper Joseph Moore who found no sign of the missing men. His preliminary search revealed the doors to the lighthouse closed, the clocks now stopped, the beds unmade and fire not lit. Returning from the Hesperus with two other’s the lighthouse must have felt eerie, having been abandoned without any visible reason. Lamps were all cleaned and filled and the only thing out of place was a chair by the kitchen table that had been knocked over. A further unusual thing was that two of the keeper’s oilskins were missing, but the third set was still in place. The lighthouse keepers log had no further entries after the day that they disappeared and a message on a slate on 15th December 1900 (which would have later been transferred to the log) indicated all was well.

A search of the island gave no sign of the three missing men. Searches of the vicinity revealed storm damage on the west landing of the island caused by severe weather, but the log indicated that this had happened prior to the last log entry of 15th December. However, a superintendent of the Northern Lighthouse Board (the general lighthouse authority for Scotland and Isle of Man), Robert Muirhead, came to Eilean Mòr on 29th December 1900 and he speculated that what had happened was that two of the keepers had gone to the western landing stage on 15th December to secure a box in which mooring ropes were stored. Then having been joined by the third keeper an exceptionally large wave had washed them away.

However, the real events of the December day will never be known. Why, for example did the third keeper leave the lighthouse (against regulations) and without the protection of his oilskins to join his colleagues. It was always made clear that the third keeper should not leave a lighthouse in a storm for any reason. Perhaps as some have also suggested, he had seen his fellow keepers in trouble and rushed to their aid, knocking over the chair on the way. However, if the men were on the west landing stage they would not have been in sight of anyone in the lighthouse nor within shouting distance. Strangely, if he was in such a panic, why had he stopped to secure the door of the lighthouse and its compound on the way to help his colleagues? The mystery remains unsolved, is likely to remain so and the bodies of the keepers were never found.

Events such as this will always attract speculation of the supernatural. It is easy to see why. These remote isolated rocky islands battered by the howling winds of the Atlantic. The high waves driven relentlessly against the cliff faces. The constant screeching of seabirds sounding like lost souls in a storm. It is said that keepers posted to the light house in Eilean Mòr after the tragedy never felt at ease there. It was thought by many to have a dark and foreboding atmosphere surrounding it and few lamented the automation of the lighthouse in 1971 which meant it no longer had to be manned. Like many such mysteries the stories surrounding the event become embellished with tales of prepared and uneaten food on the table which is something not recorded when Joseph Moore first entered the lighthouse on 26 December 1900.

Here is a poem by Wilfred Wilson Gibson (2nd October 1878 – 26th May 1962) called Flannan Isle:

Flannan Isle

Though three men dwell on Flannan Isle

To keep the lamp alight,

As we steer'd under the lee, we caught

No glimmer through the night!

A passing ship at dawn had brought

The news; and quickly we set sail,

To find out what strange thing might all

The keepers of the deep-sea light.

The winter day broke blue and bright,

With glancing sun and glancing spray,

As o'er the swell our boat made way,

As gallant as a gull in flight.

But, as we near'd the lonely Isle;

And look'd up at the naked height;

And saw the lighthouse towering white,

With blinded lantern, that all night

Had never shot a spark

Of comfort through the dark,

So ghastly in the cold sunlight

It seem'd, that we were struck the while

With wonder all too dread for words.

And, as into the tiny creek

We stole beneath the hanging crag,

We saw three queer, black, ugly birds--

Too big, by far, in my belief,

For guillemot or shag--

Like seamen sitting bold upright

Upon a half-tide reef:

But, as we near'd, they plunged from sight,

Without a sound, or spurt of white.

And still too mazed to speak,

We landed; and made fast the boat;

And climb'd the track in single file,

Each wishing he was safe afloat,

On any sea, however far,

So it be far from Flannan Isle:

And still we seem'd to climb, and climb,

As though we'd lost all count of time,

And so must climb for evermore.

Yet, all too soon, we reached the door--

The black, sun-blister'd lighthouse door,

That gaped for us ajar.

As, on the threshold, for a spell,

We paused, we seem'd to breathe the smell

Of limewash and of tar,

Familiar as our daily breath,

As though 'twere some strange scent of death:

And so, yet wondering, side by side,

We stood a moment, still tongue-tied:

And each with black foreboding eyed

The door, ere we should fling it wide,

To leave the sunlight for the gloom:

Till, plucking courage up, at last,

Hard on each other's heels we pass'd

Into the living-room.

Yet, as we crowded through the door,

We only saw a table, spread

For dinner, meat and cheese and bread;

But all untouch'd; and no one there:

As though, when they sat down to eat,

Ere they could even taste,

Alarm had come; and they in haste

Had risen and left the bread and meat:

For on the table-head a chair

Lay tumbled on the floor.

We listen'd; but we only heard

The feeble cheeping of a bird

That starved upon its perch:

And, listening still, without a word,

We set about our hopeless search.

We hunted high, we hunted low,

And soon ransack'd the empty house;

Then o'er the Island, to and fro,

We ranged, to listen and to look

In every cranny, cleft or nook

That might have hid a bird or mouse:

But, though we searched from shore to shore,

We found no sign in any place:

And soon again stood face to face

Before the gaping door:

And stole into the room once more

As frighten'd children steal.

Aye: though we hunted high and low,

And hunted everywhere,

Of the three men's fate we found no trace

Of any kind in any place,

But a door ajar, and an untouch'd meal,

And an overtoppled chair.

And, as we listen'd in the gloom

Of that forsaken living-room--

O chill clutch on our breath--

We thought how ill-chance came to all

Who kept the Flannan Light:

And how the rock had been the death

Of many a likely lad:

How six had come to a sudden end

And three had gone stark mad:

And one whom we'd all known as friend

Had leapt from the lantern one still night,

And fallen dead by the lighthouse wall:

And long we thought

On the three we sought,

And of what might yet befall.

Like curs a glance has brought to heel,

We listen'd, flinching there:

And look'd, and look'd, on the untouch'd meal

And the overtoppled chair.

We seem'd to stand for an endless while,

Though still no word was said,

Three men alive on Flannan Isle,

Who thought on three men dead.

Content type:

- Scottish

Language:

- English

- Log in to post comments