The Mystery and Legend of Celtic Hill and Promontory Forts

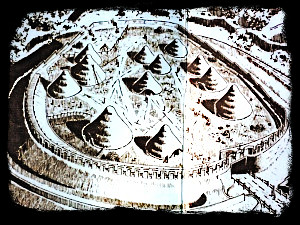

Throughout the present Celtic lands and in many of those areas once lived in by Celtic tribes, hill forts can be found. Typically they date to the Bronze and Iron Ages. Usually they followed the contours of a hill, consisting of one or more lines of earthworks, with stockades or defensive walls, and external ditches. Positioned to take advantage of the higher elevation in which they were located, they would act as a fortified refuge and defended settlement. Hill forts could be home to a significant number of people whose dwellings were built within the safety of the fortification. The hill tops on which they were built gave commanding views of the vicinity. Often they would be positioned over strategically important mountain passes or river crossings.

Many hill forts are associated with figures from Celtic legend. One such is Dùn Deardai in Scotland. Standing on a rocky knoll on Sgorr Chalum, Dùn Deardail is an Iron Age hillfort above the River Nevis in Glen Nevis. Located at a height of 1,127 ft (347m) Dùn Deardail is overlooked by the mountain of Ben Nevis (Scottish Gaelic: Beinn Nibheis) and is thought to have been constructed by the Celts in the first millennium BC (1000 BC to 1BC). The fort is associated with Deirdrê of the Sorrows, the tragic heroine in Irish pre-Christian legend, whose story is told in the ancient Irish mythology of the Ulster Cycle. Deirdrê and the three sons of Usnach were said to have lived near the fort for some of the time they stayed in Scotland.

These forts can have a mysterious element in regard to their construction. Dùn Deardail is one of a number of vitrified forts in Scotland. This is when the walls of the structure have been subjected to such intense heat that some of the stones have fused together. Vitrification has been the subject of much debate and it remains unclear why or how the walls were subjected to this process. It is known, however, that it requires very high temperatures, of around 1,000 degrees Celsius, that have to be sustained for long periods. So fires would have to be built and maintained for a number of days. Dùn Deardail has baffled those who find it difficult to explain how vitrification could work on the scale needed for this fort. It would require large amounts of fuel that would have had to be transported to the remote hilltop in the days of prehistory. The reason for doing it is also a mystery; perhaps when the fort was under prolonged attack; a possible structural component; or vitrification undertaken as a status symbol. Science fiction writer Arthur C Clarke was at a loss to explain the phenomenon and said in 2004:

The oddest thing is these vitrified forts in Scotland. I just thought, how? After all, lasers were not common in the Stone Age.

Promontory forts, commonly known in Cornwall as cliff castles, are coastal equivalents of the hill forts and can often be dated to the same period. Cornwall is a Celtic nation heavily influenced by the sea. There are many examples of promontory forts throughout the coastal areas of the Celtic lands, from the northern islands of Scotland, Ireland, Isle of Man, Wales, Cornwall, Brittany, Galicia and Asturias. Cornwall has many fine examples of these defensive structures, located above a steep cliff, connected to the mainland by a small neck of land. Their rocky sea defences providing the main protection, with ramparts and ditches required only on the narrow land connections. Possible uses of ancient Cornish cliff castles has been speculated on for many years. It is thought that their obvious defensive capability was not their only function, but they were also sites for religious ceremonies, as well as used for trade and administration purposes. It is not surprising that similar fortifications are spread around the Celtic heartlands of the Atlantic seaboard from the northern coasts of Galicia and Asturias in the Iberian peninsula. Through to Brittany, and around the coasts of the Atlantic Archipelago where the other Celtic lands of Cornwall, Ireland, Wales, Isle of Man and Scotland are located. It points to the links between these communities.

This fits in with the work undertaken by Professor Barry Cunliffe and others, that points to Celtic culture originating along the length of the Atlantic seaboard in the Bronze Age, before being taken inland into continental Europe. This stands in contrast with the once held orthodoxy that accepted the view that Celtic origins lie with the Hallstatt culture of the Alps. However, there are no accounts in Antiquity of invasions by Celts as a new incoming people into the lands of the Atlantic coast. Barry Cunliffe suggests that the Celtic people had their origins and homelands along the western Atlantic stretching from parts of the northern Iberian Peninsula, to Brittany and into what is often now referred to as the Irish and British Archipelago. The origins of the Celtic people continues to be debated.

People around the world remain intrigued by the prehistoric remains that are found throughout the Celtic lands. These monuments stand in areas of sea and mountain mists which adds to their mystery. The purpose and belief systems of the people of prehistory who erected megalithic structures may never be known. The same can also be said about Celtic hill forts and promontory forts. Some were later re-used, as is the case with Cronk ny Merriu promontory fort in the Isle of Man, when the Scandinavians arrived in Mann in the eighth and ninth centuries. However, we can never say for certain the true original purpose of all of these forts. They clearly have defensive capabilities, which suggests a perceived threat. However, there is little evidence that many were ever attacked. Hill forts show sign of human habitation, but promontory forts less so. Both could have been used for communal meeting places and to have been prestigious sites for religious ceremonies. What we do know is that we are surrounded in the Celtic lands by the remains of a society that predated the one in which we now live. Although mapping of these sites continue, with some excavation being undertaken, they remain something of a mystery.

- Pan-Celtic

- English