Gods and Goddesses of the Celtic Pantheon - Part II

The Druids were the caretakers of Celtic culture. When he came into contact with the Druids during his conquest of Celtic Gaul, Julius Caesar confirmed their religious role:

The Druids officiate at the worship of the gods, regulate public and private sacrifices, and give rulings on all religious questions. Large numbers of young men flock to them for instruction, and are held in great honour by the people.

Had it not been for the Celtic religious ban on committing the wisdom and learning of the Druids to the written word, our understanding of the Celtic Pantheon would be much greater today than it is.

Alas too few texts have survived the savagery and wanton destruction directed at the Celts over the centuries especially during the emergence of the modern nation states of England and France and the wholesale destruction in Ireland during its occupation. The surviving written Celtic source documents are due to accidents of history and geography, mainly Irish and Welsh in origin. The Folkloric traditions of all the Six Nations augment the written record and provide an important source of our knowledge of the Celtic pantheon.

This article is the second part of our survey of the Gods and Goddesses of the Celtic Pantheon. Read Part I here.

Celtic Creation Myth

Due mainly to the Celtic religious ban on committing the wisdom and learning of the Druids to the written word, we lack a creation myth in Celtic Mythology. The Druids did not record our myths. But what comes close is a beguiling tale told in "Celtic Myths and Legends" by Peter Beresford Ellis. This volume is an entertaining 600 pages of 37 mythic tales drawn from the legends and folklore of the six Celtic Nations. The opening entry is the “Pan Celtic” tale which appears after the introduction and prior to the six chapters devoted to each of the Six Nation’s folklore. I was mesmerised by this tale of the creation of the Celtic gods, Beresford’s craft creating a brilliant image as if from the Celtic equivalent of the Old Testament:

From the darkened soil there grew a tree, tall and strong. Danu, the divine waters from heaven, nurtured and cherished this great tree which became the sacred Oak named Bile. Of the conjugation of Danu and Bile, there dropped two giant acorns. The first acorn was male. From it sprang The Dagda, “The Good God”. The second seed was female. From it there emerged Brigid, “The Exalted One”. And The Dagda and Brigid gazed upon one another in wonder, for it was their task to wrest order from the primal chaos and to people the Earth with the Children of Danu, the Mother Goddess, whose divine waters had given them life.

Perhaps not the inspired word of God, but this one paragraph is an amalgamation of the creation of the Celtic Pantheon. Dagda, the chief God of the Celts, the majestic Brigid who was worshiped throughout the Celtic lands, and Bile, whose role was transporting the souls of dead Celts to the Otherworld. Also included are the children of the Mother Goddess Danu, the Tuatha de Danann, who are fundamental to Scottish, Irish and Manx Mythology.

Danu

Celtic scholars agree that Danu is the name of a deity that ranked high in the Celtic Pantheon dating from the earliest history of the Celtic peoples. Danu was most likely the Celtic Mother Goddess and that she gave her name to the Tuatha Dé Danann (Children of Danu). But beyond this point the Celtic scholars diverge on the identity and origins of Danu. A mystical figure shrouded behind the curtain of lost knowledge that died with the last Druid. There is general agreement that Danu is related and cognizant with the Irish deity Anu, referred to as the mother of the gods of Ireland, and the Welsh deity Don, a mother fertility goddess. The similarity in spelling and the fact that Anu and Don are female deities related to the fertility of the land allows for the argument that Anu and Don are strongly connected to Danu and may be the same goddess in Irish and Welsh form thus merging the Goidelic and Brythonic branches of Celtic culture and language. Patricia Monaghan in the Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore has the following entry on Danu: “Most significantly, we find an Irish divine race, thought to represent the gods of the Celts, called the Tuatha Dé Danann, the people of the goddess Danu”. Similarly we have this entry from the Dictionary of Celtic Mythology by Peter Beresford Ellis: “A mother goddess from whom the Tuatha Dé Danann takes their name. If her (Danu) counterparts in the Welsh tradition are anything to go by, Danu’s husband was Bile, god of death. The Dagda is her son. https://www.transceltic.com/pan-celtic/danu-myth-goddess-band

Brigid

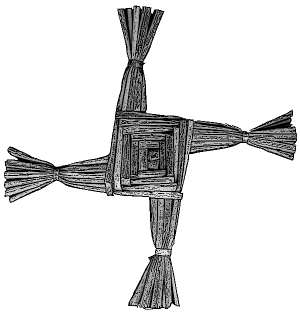

This modern Christian Saint serves as a classic example of the merging of Celtic and Christian traditions. A Christianised Celtic Goddess, Brigid is said to have been the daughter of the Dagda who was father figure and Druid of the Tuatha Dé Danaan. It is arguable that nothing typifies more the successful tactics of the Christian conversion of Ireland than the fate of Brigid. One is tempted to weep to imagine how she suffers having spent the past 1600 years confined to the rigid confines of the Christian liturgy. To promote their new religion, a new and confusing theology to the Gael, the soldiers of St. Patrick transformed Brigit into a Christian rather than a Celtic deity. In the early tales of the Christian Saint, Brigid is portrayed as the daughter of a Druidical household before her embrace of the new religion. Thus with her conversion to Christianity, Brigid abandons the Celtic Gods and their priests. To reinforce this transition the early church adopted Imbolg, the feast day of the Celtic Goddess Brigid, to the feast day of the Christian saint. “As goddess, Brigid is a rarity among the Celts, a divinity who appears in many sites. Her name has numerous variants (Brigid/Brigit/Brid/Brighid). As Celtic divinities tended to be intensely place bound, the apparently pan-Celtic nature of this figure is remarkable. The Irish Goddess ruled transformation of all sorts: through poetry, through smith craft, through healing. Associated with fire and cattle, she was the daughter of the (immensely powerful) god of fertility, the Dagda.” (Monoghan)

Kelpie

In some stories Kelpie are described as ‘shape shifters’. They are able to transfer themselves into beautiful women who can lure men and trap them. However, the Kelpie does not always take a female form and are mostly male. They are also described as posing a particular danger to children when in the shape of a horse. Attracting their victims to ride them they are taken under the water and then eaten.

In some stories Kelpie are described as ‘shape shifters’. They are able to transfer themselves into beautiful women who can lure men and trap them. However, the Kelpie does not always take a female form and are mostly male. They are also described as posing a particular danger to children when in the shape of a horse. Attracting their victims to ride them they are taken under the water and then eaten.

A Kelpie in the Celtic mythology of Scotland was originally a name given to a ‘Water Horse’. This supernatural entity could be found in the lochs and rivers of Scotland and also has a place in Irish folklore. The description of their appearance can vary in different tales. Some of these variations and the stories associated with the Kelpie are regional in origin. Known as shape shifters, the Kelpie are able to transfer themselves into beautiful women who can lure men and trap them. However, the Kelpie does not always take a female form and are mostly male. They are also described as posing a particular danger to children when in the shape of a horse. Attracting their victims to ride them they are taken under the water and then eaten. In Orkney a similar creature exits known the “Nuggle” which also takes the form of a horse and waits by the waterside. Any human mounting the horse is taken into the river or loch and drowned. In the Shetland Islands the water horse is known as “Shoopiltie” and again lures people to ride but then plunges into water with its doomed human cargo. Versions of this creature exist in the other Celtic nations. In Wales the “Ceffyl Dŵr” is another spirit associated with water. A shape shifter that can also take the form of a horse, sometimes with wings that can take any unfortunate rider into the air from where they plunge to their death. In Manx mythology there is a water horse known in Manx Gaelic as "Cabbyl-Ushtey" and also associated with another creature of streams and river the “Glashtyn”. https://www.transceltic.com/scottish/kelpie-mythical-water-horse-folklore-scotland

Cailleach the great Gaelic Goddess of Winter

In Gaelic mythology (Irish, Scottish and Manx) Cailleach is a creation goddess. She is commonly known as the Cailleach Bhéara and in Scotland also as Beira, Queen of Winter. In partnership with the goddess Brìghde, they rule the seasons. Cailleach governs the winter months between Samhainn (1 November ) and Bealltainn (1 May), while Brìghde rules the summer months between Bealltainn and Samhainn. It is said that Cailleach carries a staff that freezes the ground. Cailleach is credited with making numerous mountains and large hills. Across the Gaelic world there are a number of locations named after her such as Ceann Caillí the southernmost tip of the Cliffs of Moher in County Clare, Ireland. There are also ancient stones and burial mounds that are associated with Cailleach and have legends attached to them. Such as Glen Cailleach which joins to Glen Lyon in Perthshire, Scotland. The glen has a stream named Alt nan Cailleach. There is a small Shieling (hut) in the Glen, known as Tigh nan Cailleach which has a number of carved stones. Local legend says they represent the Cailleach, her husband the Bodach, and their children. It is said that Cailleach and her family were given shelter in the glen by local people. When they left they gave the stones to the locals and vowed that as long as the stones were put out to look over the glen at Bealltainn then placed put back into the shelter for the winter at Samhainn then the glen would continue to be fertile. This is a ritual that continues to be followed. https://www.transceltic.com/blog/cailleach-great-gaelic-goddess-of-winter

Content type:

- Pan-Celtic

Language:

- English

- Log in to post comments