Brigid - Celtic Goddess To Christian Saint - The Feast of Imbolg

During the period of Christian conversion of Ireland in the 4th and 5th centuries, it was the strategy of monastic scholars to ensure an easy transition from Celtic to Christian belief. The disciples of Saint Patrick successfully deceived the Celts into thinking that the new faith of Rome was a mere extension of their traditional religion.

Christian missionaries incorporated elements of the peoples veneration of the Celtic Gods into Christian doctrine. The often used example of this religious shift is the fate of Brigid. Brigid was deftly transformed from a daughter of ‘The Dagda’ of the Tuatha Dé Danann into the Saint of the same name. In the early tales of the Christian Saint, Brigid is portrayed as the daughter of a Druidical household before her embrace of the new religion. The Druids were the priests of the pagan Celtic religion but were also akin to today’s upper middle classes: “The Druids were the professionals of pre Christian Celtic society. They comprised all the professions – doctors, lawyers, teachers, philosophers, ambassadors...(and priests of the Celtic Faith)” (Ellis). Thus with her conversion to Christianity, Brigid abandons the Celtic Gods and their priests, the Druids. To reinforce this transition the early church adopted the feast day of the Celtic Goddess Brigid, or Imbolg, to the feast day of the Christian saint.

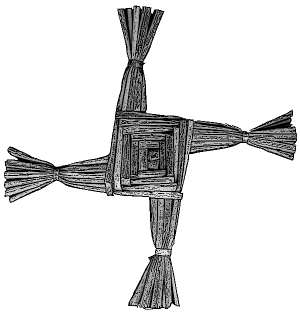

Imbolg, observed on the first day of February, is the second of the four ancient yearly Celtic Festivals, representing the advent of the traditional agricultural year. It is a pastoral holiday marking the start of the lactation of domesticated sheep, an important annual milestone to the pastoral Celt. Imbolg is connected with the Celtic goddess Brigit because Imbolg is the same day as the Festival of the Goddess Brigit. The exact same day.

Christians recognise Brigit as an Irish Saint, second only to St. Patrick and ranking with St. Columba. But the pagan deity of the same name had a much wider influence. There is archaeological evidence of the Celtic Goddess Brigit being worshipped not only in the modern Celtic nations but in pre-Roman continental Europe during the period of Celtic cultural hegemony, a time when the Celts held sway from the British Islands to the Black Sea. Patricia Monaghan in "The Encyclopaedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore" continues on the same line:

As goddess, Brigid is a rarity among the Celts, a divinity who appears in many sites. Her name has numerous variants (Brigid/Brigit/Brid/Brighid). As Celtic divinities tended to be intensely place bound, the apparently pan-Celtic nature of this figure is remarkable. The Irish Goddess ruled transformation of all sorts: through poetry, through smith craft, through healing. Associated with fire and cattle, she was the daughter of the (immensely powerful) god of fertility, the Dagda.

Thus emerges the picture of Brigid, the Exalted One, a majestic deity who spanned the Celtic world at its most powerful. A deity that Christian Monks who, upon their penetration of the Celtic homelands in the 6th century after the collapse of the Roman world, could not ignore. So they set about transforming Brigid, the “Exalted One” of the Celtic pantheon, and the daughter of Dagda, to a Christian Saint to be used as a potent weapon in their war on the pagan beliefs of the Celts.

In an article published by Transceltic on October 25, 2013 entitled Interview with Dr. Jenny Butler: The Celtic Folklore traditions of Halloween, we asked Dr. Butler to explain how the pagan feast day of Samhain (Halloween) become a holy day of the Catholic Church and if she saw a parallel in the merging of Imbolg, the Feast Day of the Celtic Goddess Brigit, into the Feast Day of the Catholic Saint Brigit. Dr Butler is a Folklorist and Lecturer at University College Cork's Folklore and Ethnology Department and a member of The Irish Society for the Academic Study of Religions. Dr. Butler has numerous articles to her credit and is currently working on a book about Irish contemporary Paganism. According to Dr. Butler:

"The pagan festival of Samhain (Halloween) did not directly morph into a Catholic holy day. In fact, All Saints Day was originally held on May 1st, but was moved to November 1st in the year 834 and the festival became fixed at November 1st on the Gregorian calendar. All Souls’ Day follows the day after All Saints’ Day. On November 2nd for All Souls’, Roman Catholics pray for the faithful departed souls who are in purgatory. ‘Halloween’ is etymologically related to the Christian festival of All Hallows Day, Hallowmas or All Saints’ Day on 1st November, as follows: ‘Hallows’ derives from the Old English word hālig, meaning ‘holy’. Hallow means ‘to make holy’ and before the year 1121 halgod (past participle) was used. Later, halwen and halowen (about 1300) were used and about the year 1745, the Scottish shortening of Allhallow-even (for All Hallow’s Eve) became Hallowe’en. It is likely that the holy days of All Saints and All Souls were placed near Samhain since it coincided with an already existing feast of the dead."

"In relation to the Celtic Feast Day of Imbolg there is a clearer merging of pagan and Christian traditions. Brigit is a Christianised goddess who is associated with the spring festival. St Brigit’s feast day is February 1st and this is also the traditional marker of the beginning of spring. The Old Irish name for the festival is Oimelc, possibly meaning ‘ewe’s milk; lambs are born at this time of year and ewes come into milk at this point so that they will be able to feed the lambs during the coming season. The word imbolc or Imbolg, ‘im’ ‘bolg’, likely meaning ‘in the belly’, might also refer to lambing season. The Irish goddess Brigit is associated with human and animal lactation. She was said to be the daughter of the Dagda, one of the principle gods in the Celtic pantheon, and the wife of Bres, a half-Fomorii God. Although it is thought that people throughout Ireland venerated this goddess, she is particularly associated with the province of Leinster and she may have been the sovereignty goddess of that region. Her chief shrine was in Kildare, where priestesses tended her vigil fire. The shrine of Brigit was taken over by nuns and in legend these nuns continued to tend the sacred flame of Brigit at that same location in County Kildare until the thirteenth century, when the Bishop of Kildare decreed that the custom was pagan and therefore must cease. The goddess Brigit is a pan-Celtic deity and there are parallels in Britain with the worship of Brigantia, a name that means ‘high one’ or ‘queen’ and the name Brigit is thought by some scholars to be an epithet meaning ‘exalted one’. Another possible parallel is the Goddess Brigindo, worshipped by the Gauls. With the Christianisation of Ireland, the goddess Brigit became St Brigit and customs to do with the spring fertility festival were attached to St Brigit’s feast day in popular tradition. The correlation between Christian holy days and the earlier pagan religious festivals is even clearer in this case than in the case of Samhain."

It is arguable that nothing typifies more the successful tactics of the Christian conversion of Ireland than the fate of Brigit, the daughter of Dagda (a principal god of Celtic mythology). One is tempted to weep to imagine how she suffers having spent the past 1600 years confined to the rigid confines of the Christian liturgy. To promote their new religion, a new and confusing theology to the Gael, the soldiers of St. Patrick transformed Brigit into a Christian rather than a Celtic deity

Miranda Green in her work the Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend characterises the transition from Celtic Goddess to Christian Saint:

The name of the Irish goddess was originally an epithet meaning "exalted one". Brigit is of special interest because she appears to have undergone a smooth transition from Pagan Goddess to Christian Saint. As a saint, Brigit took over many of the attributes of the pagan goddess. Her birth and upbringing were steeped in magic. She was born in a Druid’s household and fed on the milk of magical, Otherworld cows. As a Saint of Kildare her fertility symbolism is intense, even though she herself was a virgin. She supplied limitless food without her larder ever dwindling; she could provide a lake of milk from her cows. But the most significant factor in the transition is that the feast day of St. Brigit took place on 1 February, Celtic feast of Imbolg, which was the Festival of Brigit the goddess.

However, the elimination of Celtic pagan religious practices proved a daunting task, so much so that the 7th century Pope Gregory was prompted to decree:

Take advantage of well-built temples by purifying them from devil worship and dedicating them to the service of the true God.

And it was in this spirit that the shrine at the Kil Dara (the temple of the oak), a pagan sanctuary built from the wood of a tree sacred to the Druids and which was dedicated to the Celtic Goddess was changed into a Christian shrine. The ritual fire of the Druids, which honoured Brigit, was extinguished and a new flame lit in deference to the Christian Saint. Thus the disciples of Saint Patrick adopted the pre-Christian practices of the Celts so that the new religion was viewed as a continuation of their ancient beliefs.

There are four great Feast Days of the Celtic Year:

- Samhain - the Celtic New Year (Halloween) celebrated on November 1st

- Imbolg - the Feast of the Goddess Brigit on February 1st

- Beltane – festival honouring the beginning of summer

- Lughnasadh - the harvest festival and last feast day in the year which falls on August 1st

Recommended further reading

Patricia Monaghan's "The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore"

Get your copy from Amazon.com (US$) or Amazon.co.uk (GB£):

Content type:

- Pan-Celtic

Language:

- English