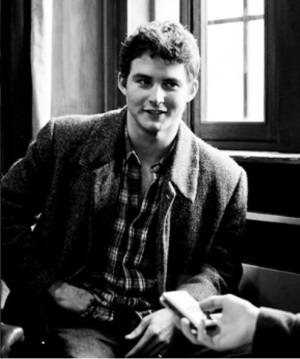

The Fight To Save Our Language, Our Nations, Ourselves: Introducing Liam Alastair Crouse

Celtic Culture is anchored in the languages of the Six Nations. Indeed, the definition of a modern Celtic nation is based on language and it is widely recognized that the each of the six national languages face challenges of varying degrees. Guarded optimism coupled with vigilance and determination to fight back from the centuries of systematic persecution and suppression of the Celtic languages must be our mantra if we are to restore Breton, Cornish, Welsh, Manx, Irish and Scots Gaelic to their rightful positions.

In a January 2013 interview with Transceltic, the noted Celtic historian and author, Peter Beresford Ellis, shared his insights into the current state and future of the tongue:

In spite of the achievements of the last decades, there is no room for complacency when examining the current situation and looking to the future (of the Celtic languages). Coming from the 1960s perspective when Welshmen and women were going to jail in their campaign to gain status for Welsh; when the Cornish who proclaimed their Celticity were sneered at as fantasists dreaming of the second coming of King Arthur; when Scottish Gaelic speakers could not even register their children in the language … well – times have moved on. Since the 1960s there has been some legal recognition given to the Celtic languages and through this there is a more widespread knowledge of the languages and their historic, cultural and social value. But the fact remains, they are still endangered languages. Look at recent Census figures for Welsh as an example. There is no easy acceptable programme to ensure their salvation. It comes down to hard work – we must publicise, educate and encourage. There is a saying in each of the six Celtic languages – no language, no nation!

The survival of the language in each of the Six Nations is in the hands of future generations. And it is in that spirit that Transceltic are honoured to welcome Liam Alastair Crouse as a contributor. Liam’s Blog Posts will focus on his experiences in Scotland as he works to revitalize the Scots Gaelic tongue. Liam is currently a post-graduate student in Publishing Studies at the University of Stirling, after having obtained his under-graduate degree in Celtic and Archaeology from the University of Edinburgh. He will be focusing on Gaelic literature in his studies and is working closely with the Gaelic Books Council. He is originally from Rhode Island in the US and is both a Gaelic speaker and a Piper. Scottish Gaelic tradition, history, and culture are the driving interests in his life.

A Celtic Awakening, by Liam Alastair Crouse

I once went to Cape Breton, home to one of the last vestigial Scottish Gaelic immigrant communities in existence outside of Scotland. I was 17, enthralled by all things Scottish. I had harbored a great love of the Scottish for a few years by then, despite never having visited the Old Country. I took along my pipes, excited by the thought of piping the sunsets down on the side of mountains. And I did. It was all very romantic.

When the time came to choose universities, there was no choice – I applied to the four ancient universities in Scotland, and no others. I was pretty set in my way – I was going to Scotland, and that was that. The course I eventually picked was Scottish Ethnology and Archaeology, at the University of Edinburgh. ‘Do what you love, and you’ll love what you do’, as an adult once told me.

In my first few days at the university, I sat down with my Director of Studies to decide my extra module. On offer was anything in the College of Humanities: Rhetoric, Scottish History, Women’s Literature – you name it, the University of Edinburgh had it. And my eye strayed to Scottish Gaelic. Languages – I had never been “good” at languages; Spanish and Latin in high school had not necessarily been strong points. But the idea of studying the ancient language of Scotland drew me in more than any apprehension pushed me away. So I took it, the passing murmurs of a language which I had heard in Cape Breton only a stirring in the back of my mind.

Learning new languages is not necessarily easy. But, the further along you go, and the further in you get the more alluring and effortless it becomes. Well, when I went into that class, Gaelic 1A, I wouldn’t have even imagined what would come out the other end.

I remember the pivotal point of no return. Before I left, I had decided I would stay in Scotland for Christmas. I booked a one-way ticket. My parents, understandably, had warned me about such actions; it was after all, the longest period of time I had been away from home (not to mention living in a different country). Yet, I had gone all-in in my poker bet.

During the gloomy stay in halls during the winter (the lack of sunlight coupled with the lack of other students was duly noted), I was fortunate enough to meet up with a local of Edinburgh who was a native Gael (i.e. Gaelic speaker) of Canadian/American extraction, a piper, and a tradition bearer of Gaelic lore. He mentioned that he was travelling to Inveraray in Argyll for Hogmanay to visit a few friends and invited me along.

After a bus journey, which included hours of riveting discussion about Highland history and culture, we arrived along the shoreline of Inveraray and were met by a local lad. He whisked us away to a weekend of first-footing, revelry, hiking, songs, piping, and discourse (and whisky) which took place in his small, old-fashioned house up in the middle of the glen.

Those few days probably changed me more than any other. I gained an insight into Highland culture unlike any I had received from my books – a tangible link to a life which has, in other places, been met with extinction. And it was still a bit romantic.

Since that time, I have matured into a fluent Gaelic speaker, a vastly superior piper, and even a bàrd, composing verse in Gaelic. And over the years of learning the language, I have mellowed. There are many draws to learning Gaelic: a close community (if you chose to take part), joviality, music, tradition, history, and so on. There are also many drawbacks: it is a difficult language to learn (and not just because of the pronunciation or the syntax, but because it’s hard to get practice), there are those who do not understand why someone would learn a “dying” language (and they are rather ‘vocal’ (read irritating) about it), and the fact that the future of the language is by no means certain yet. But perhaps most importantly, once you learn Gaelic, you have a personal obligation to keep it alive.

One way that I’ve come to fulfill my obligation is through publishing. I was very fortunate to be encouraged to come to Gaelic publishing, an industry which straddles the line between hobby and profession. It is by no means an easy task, presenting difficulties of literacy rates, market size, and proportionally small arts funding. There are also very few job opportunities: one of the two major publishers operates on a voluntary basis.

Yet, Gaelic publishing, along with the broader industry, is going through some pretty interesting times. In Gaelic we are faced with questions concerning e-books, pricing, genre improvement, and so on. The successful and well-known Gaelic fiction series, ‘Ùr-sgeul’, which drew to a close last year, was designed to develop adult fiction. It gave a chance for established authors to produce materials, as well as giving emerging authors a platform from which to operate. The focus now is shifting to the creation of more Gaelic publishers, of which I may be considered a test-dummy.

Gaelic has been expanding in recent years into domains which it has never been a part of before. It has done this despite a continued decline in numbers (although this degeneration has stagnated in some sectors).

We need to implement new schemes in order to foster the growth of both Gaelic learners and the re-strengthening of the traditional Gaelic-speaking areas.

I’ll leave you with words from the famous Gaelic bàrd, Murchadh MacPhàrlain (as was quoted in another blog recently). While being interviewed for a documentary, he told the journalist:

I envy you people. Just imagine going home tonight and thinking that the language you speak will be dead in another 60 years. Just imagine that. It’s so discouraging. Yet still we sing, still we make songs, in spite of everything.

And I say, to anyone at all interested in learning the language, come, come and sing with us. And I’ll buy you a dram.

- Pan-Celtic

- English

- Log in to post comments