Ravens in Celtic and Norse Mythology

Animals and birds are a significant feature in Celtic and Norse mythology. We know that the Celts had and continue to hold a great respect for the environment. Nature, the elements and the other creatures which shared their land held a sacred significance. Animals and birds were vital to everyday life and wellbeing and they feature in art, literature, rituals and religious beliefs. We recently wrote about the horses in Celtic mythology.

In the Celtic world there have been many Scandinavian and Viking influences over the centuries that remain evident today. The Viking incursions in the Celtic lands began in the 8th century. All of the present six Celtic nations felt the impact of the Viking raids. They brought with them their legends and sagas the legacies of which are found in literature, folklore and carvings in many parts of the Celtic lands. As with the Celts animals and birds affected the everyday life of the Norse people and held a crucial place in their belief systems. In this article we take a particular look at the place of ravens, crows and their relatives in Celtic and Norse mythology.

Ravens and Crows

The scientific name for ravens, crows and their relatives is Corvidae. There are over 120 species and they include ravens, crows, rooks, choughs, jackdaws, and magpies. In Celtic mythology the Raven features in many legends. This large bird feeding as it does on carrion with its black plumage and disturbing deep hoarse croak is often viewed with some foreboding for it can be seen as an omen of death. It can also be associated as a source of power, straddling as it does the worlds of the living and the dead therefore often depicted as messenger between the two. Ravens hovering over the scenes of battle, ready to swoop down on the bodies of the fallen must have been a fearsome sight to Celtic warriors. Little wonder then that they could be seen as having the power of gods.

In Irish mythology the war goddess Badb features in the story of Táin Bó Cúailnge which is the central tale in The Ulster Cycle. Taking on the form of a crow or raven she causes terror amongst the forces of Queen Medb of Connuaght in the battles fought with Ulster and the legendary hero Cú Chulainn. It is also said that the Morrigan, in the form of a raven, perched on Cú Chulainn’s shoulder at the time of his death.

In Welsh mythology the figure of Bendigeidfran appears in the Welsh Triads (Welsh: Trioedd Ynys Prydein) a set of medieval manuscripts that contain Welsh folklore. Bendigeidfran or Brân Fendigaidd (his name can be translated as Blessed Raven) also features in the second branch of the Mabinogi. Ravens also appear in the Dream of Rhonabwy (Welsh: Breuddwyd Rhonabwy) and recounted in Red Book of Hergest (Welsh: Llyfr Coch Hergest) written in the fourteenth century. The story is set at the time of Madog ap Maredudd a prince of Powys who died in 1160. It tells the story of the dream of his retainer Rhoanbwy where he visits the days of King Arthur. He dreams of a figure in Arthurian legend Owain mab Urien and sees the time when Owain and Arthur were playing chess. At the same time some of Arthur’ attendants were tormenting Owain’s ravens. Arthur ignores Owain’s request that this be stopped. In revenge Owain’s ravens kill many of Arthur’s attendants before peace is restored.

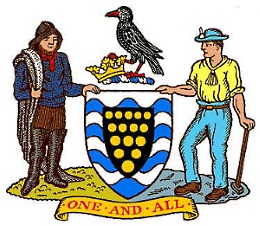

It is said in Cornish folklore that King Arthur did not die but his spirit entered into that of a red billed Chough, a member of the crow family. The red feet and beak of the bird are said to represent the violence of his last battle. The red billed Chough has particular cultural connections to Cornwall and it appears on the Cornish coat of arms. It is deemed very unlucky to kill this bird. Although there had been a marked decline in the Cornish Chough over the years an ongoing conservation effort continues to be under way to support and promote suitable habitats that will see more breeding pairs.

In Norse mythology the raven holds a special place. The god of the Æsir pantheon Odin is sometimes referred to as the Raven God. This is due to his association with the ravens Huginn and Muninn as referred to in the Poetic Edda, a collection of old Norse poems compiled in the 13th century from earlier sources. These two birds fly around the world gathering information and relay it all to Odin. Odin is also said to have two wolves, Geri and Freki who sit at his feet whilst Huginn and Muninn perch on his shoulders. On the Isle of Man (Mannin) there are a large number of carved Celtic stone crosses; many carry Celtic designs and inscriptions using an early Celtic script called Ogham. There are also a number of Norse crosses with images of Norse pagan mythology and runic inscriptions. One of these is Thorwalds Cross, dating to the 10th century, which depicts Odin with a raven at his shoulder. It also shows the wolf Fenrir biting Odin in the events of Ragnarök which fortells the death of Odin and other major Norse gods.

Ravens also feature in the stories of the Valkyrie in Norse mythology. They are female figures that choose who will live and die in battle. Of these they select some who will go to Valhalla (hall of the slain), located in Asgard home of the Æsir gods. Here they would prepare to aid Odin in the forthcoming battles of Ragnarök where the old world would die and new world would begin. In the 9th century poem Hrafnsmál a meeting is described between one of the Valkyrie and a raven where they discuss the life and exploits of Harald Fairhair (Old Norse: Haraldr hárfagri) first king of Norway.

The importance of the raven to Vikings is shown by how often the bird’s image is used. It features on armour, helmets, shields, banners and carvings on longships. No doubt the intent was to invoke the power of Odin and this would not have been lost on the enemies that they were about to engage in battle. Many of the Norse-Gael leaders continued to use the image as did the Norse Jarls of Orkney. Even today the yearly Viking festival of Up-Helley-Aa in the Shetland Islands of Scotland uses the image of a raven.

Protection and Conservation

These are just some of the legends in Celtic and Norse mythology that put the raven at centre stage. However, many other birds feature in the folklore of the Celts and Norse. Their importance is just as great now, but not only in mythology and legend. The flora and fauna within all of the lands of the Celtic nations is something to be celebrated and cherished. Our environment is an important part of us as a people and needs to be protected as equally as our language and culture. Our landscape, geographic location and wildlife has played a pivotal role in our history, beliefs and recognition of ourselves. For our culture tells us that we are part of and completely tied to the lands in which we live or from whence we came.

There is a pressing need to protect birds and wildlife throughout the Celtic lands and beyond. Wherever you are in the world remember the importance of nature and the environment. Now more than ever birds and all wildlife need our help. So, if you can, seek out those organisations that are involved in conservation and find out the schemes that they are undertaking to protect nature. You might be able to help. Here are just a few of such organisations:

External Links

Irish Wildlife Trust

An Taisce/The National Trust for Ireland

Scottish Wildlife Trust

Nature in Shetland

Fair Isle Bird Observatory

Visit Orkney

The Hebridean Trust/Urras Innse Gall

Tourisme Bretagne nature

Manx Wildlife Trust

Natur Cymru

Cornwall Wildlife Trust

Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust

RSBP

RSBP Scotland

LPO

Content type:

- Pan-Celtic

Language:

- English

- Log in to post comments