Origin of the Celts - "Celtic From The West” Theory Puts Celtic Homelands On Western European Atlantic Coast

Celtic Hegemony In Europe And Beyond At Its Height

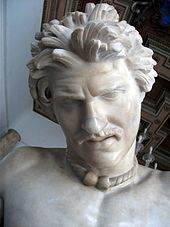

At one time the Celtic peoples were spread over large parts of Europe and beyond. It is known that by around 275 BC, the Celts' influence and power stretched from the Atlantic seaboard in the west of Europe and included parts of the Iberian peninsula, the islands of Britain and Ireland, much of Western and Central Europe, part of Eastern Europe and into central Anatolia. There can be little doubt that the Celts viewed themselves in that period as an identifiable separate ethnically similar people speaking related Celtic languages. Sculptures carved at the time and found in many parts of Europe project a similar image of themselves over a significant geographical spread.

The question of where the Celts originated prior to this great expansion has been the subject of much research over recent years. In particular the hypothesis of “Celtic from the West”, raised by a number of those studying the subject including Barry Cunliffe archaeologist and academic, who was Professor of European Archaeology at the University of Oxford from 1972 to 2007 and now Emeritus Professor and his colleague John T. Koch, who is an academic, historian and linguist who specializes in Celtic studies. The theory being that the Celtic-speaking peoples emerged from the communities living along Europe’s western coastal regions during the Bronze Age.

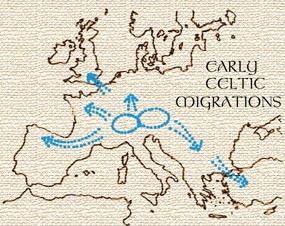

This idea challenges that once almost universally held view that the origins of the Celts lie with the Hallstatt culture of the Alps. Certainly Roman and the classical writers in the 4th century had positioned the Celts as being from that part of Europe to their north. This later understanding was informed by the first contact that the Romans had with the Celts. There was clearly a spread of the Celts south and east with a migration of Celts from about 400 BC from the area north of the Alps into the Po Valley, moving downwards to the south. This happened as Rome was developing and moving northwards and so the Romans came into contact and engaged in battle with the Celts.

Later still, in the third century BC, groups of Celts spread down from the Hungarian plains and from what is now known as Serbia into Greece and Delphi. They returned north, but some moved across the Dardanelles, crossing the Bosphorus into Anatolia in Central Turkey and settled there. They used the term Galatians to describe themselves. In classical history the description Celt, Gaul and Galacian were interchangeable. That spread of the Celts south and east is clearly backed by evidence. It therefore seemed logical to later scholars that there was a wave of migration to the west at the same time. They also identified that there were connections and a distribution of material culture that linked the Celts in the east of Europe and those on the Atlantic coast, the British Isles and Ireland. This gave one reason why earlier historians, having established that there were movements of Celts south from the Alps, thought there must also have been a migratory movement westwards at this time.

This traditional view was also developed over the last three centuries. In the 17th century, often influenced by Biblical stories, scholars such as Aylett Sammes in 1676 believed that Europe was populated by movements from the east. A view that formed the basis for the work of Paul-Yves Pezron, L'Antiquité de la nation et de la langue des Celtes (1703). This would provide the historical model adopted by Edward Llhuyd to explain the appearance of Celtic languages in Britain, Ireland and Brittany in his Archaeologia Britannica (1707). A pioneering linguist, he visited every county in Wales, and then travelled to Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall, Brittany and the Isle of Man in pursuit of his studies. There can be no doubt of the significance and influence of this body of work at the time. However, thereafter the idea of Celtic waves flowing westwards from central Europe became an established dogma, which was surprisingly left largely unchallenged for many years. The past view was that the remaining Celtic languages of Breton, Cornish, Irish, Manx, Scottish and Welsh were an old remnant of the migrations from the continent who brought their languages with them in around 400 BC.

New View Of Celtic Origins

A more recent view of Celtic origins points to it having evolved from Europe’s Atlantic western coastal areas. Interesting cultural similarities exist along the western seaboard of Europe, stretching from the Iberian Peninsula, along the Atlantic coastline and up to Ireland and northern Scotland. It appears logical that in ancient times the sea was one of the fastest and easiest ways to travel. Increasingly the evidence points to the Celts having gradually emerged as a distinct peoples from the Neolithic communities dwelling in what has been described as the Atlantic Zone of western Europe. Sea routes in prehistory along the Atlantic zone allowing for trade, communication and population movement. Stretching back to the hunter gather period 6000 BC - 5000 BC burials along the Atlantic seaboard showed very similar burial rights. The great megalithic structures that were created from the fifth to first millennium BC point to the degree of contact and shared practices between these people. The similarity in burial practices, carved tomb designs and astronomical alignment are remarkable.

It seems that people were in constant contact, exchanging ideas and trade along the Atlantic zone. Continuing into 2000 BC in what is known as the beaker culture and into 1000 BC (late Bronze Age). So from the Mesolithic period to the Iron age and into Roman period this Atlantic trade and shared ideas and concepts continued. In regard to Celtic languages there has been a considerable body of work undertaken by American academic, historian and lingusit John T. Koch. He has brought forward a body of research based upon archaeological evidence of the Celtic language being written in Pheonician script from western Iberia as early as the 8th century BC. However, an interpretation of new evidence is that the Celtic language, and the belief systems associated with it, originated in the Atlantic zone of Europe at least in the fourth millennium and spread eastwards into middle Europe in the third millennium. This fits in with the view of the early classical writers of Greece, writing in the 6th and 5th century BC, who pointed to the Celts having come from the western extremities of western Europe and Iberia.

New Evidence And Techiques Can Lead To A Different View Of Celtic Origins

Just as it has been right to challange the old dogma and traditional theories about the origins or homeland of the Celtic speaking peoples being in Central Europe. It is also right that new hypotheses based on new evidence and techniques should be brought forward to test the theory that points to a west European and Iberian origin of the Celtic people in the Late Bronze Age or earlier. All views of history have to be prefixed with the words "evidence to date”. This does not mean that this view of the origin of the Celts will remain static. New evidence and DNA research findings are being put forward all of the time. This includes that being undertaken into migrations after the mesolithic period about 6000 years ago. Then into the 3rd Millennium BC, which corresponds with Bell Beaker/Beaker culture. A lot of more recent work concentrates on burial sites. With Ancient DNA samples being taken in Ireland that reflects these movements. One being from a henge monument in Ballynahatty monument in Ireland dating 3343 - 3020BC and the other from the Bronze Age Rathlin Island burial site in Ireland. These studies seek to match the DNA being found with modern populations.

As far as the Celtic languages are concerned this more recent DNA evidence points to the possibilty that the Indo-European languages arrived in the Celtic areas in about 2400 BC, which is the early Beaker period. However, because there is genetic continuity from this period, the Celtic languages of Giodelic and Brythonic would have evolved within these communities. There continues to be no evidence to date of further influx in the Late Bronze Age of 1300 to 800BC into the areas where these languages are spoken. This includes from the period after that and around 400BC when the Celts north of Italy came into the Poe Valley and then further south. That happened, but there is no evidence that they spread west towards what we now see as the modern Celtic lands. This all points to the origin of the Celts being the western coastal areas of Europe and a spread eastwards along rivers and other trade routes eastwards into other parts of Europe and beyond.

Further Information

Further information can be obtianed from the three 'Celtic from the West' books, each a follow up to the other, edited by Barry Cunliffe and John T. Koch. A previous lecture by Barry Cunliffe on Celts from the West is posted below and gives a good summary of the subject.

- Pan-Celtic

- English