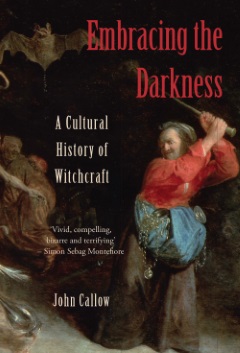

Interview with John Callow on his new book ‘Embracing the Darkness - A Cultural History of Witchcraft’

John Callow is a writer and historian, specialising in Seventeenth Century politics and popular culture. He is the author of 'The Making of James II', 'Witchcraft and Magic in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Europe', 'King in Exile' and 'James II -The Triumph and the Tragedy'. His new book ‘Embracing the Darkness. A Cultural History of Witchcraft’ has just been published by I.B. Tauris.

John is of Manx descent and alongside his books he is the author of the articles on 'The Limits of Indemnity: Sovereignty and Retribution at the Trial of William Christian (Illiam Dhone)' (Seventeenth Century, vol.XV. no.2), ‘Thomas Fairfax as Lord of Man’ (in England’s Fortress – New Perspectives on Thomas, 3rd Lord Fairfax) and a study of ‘Lieutenant John Hathorne & Garrison Government on the Isle of Man, 1651-60 (Isle of Man Studies Vol.XIV).

Interview with John Callow

Q 1. What inspired you to write a book on this particular subject matter?

Witchcraft is such a wonderful and darkly fascinating project that it’s a gift to any author. ‘Embracing’ is a natural progression from ‘Witchcraft & Magic in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Europe. My earlier book, with Geoffrey Scarre, was primarily an intellectual history – seeking to explain why the elites and universities were so keen to evolve complex theories in order to underpin and justify a belief in witches. By way of contrast, ‘Embracing’ sets out to add colour, shade and nuance: in order to explain why the figure of the witch has been so potent within the Western imagination over the last 3,000 years.

Along the way you’ll encounter, through the book, a 1st century North African magician; a German city gripped by the paranoia of a full-blown witch hunt; Herne ‘the Hunter’; the Brothers Grimm; and the artist (Durer) who first defined the archetype of the European witch and his pupil (Baldung Grien) who did more than anyone else to brutalise that image.

Q 2. Clearly considerable preparation and research went into writing this book. How long did this all take and did this take you into areas of research that you had not originally intended?

It took longer than it should! Trying to fit research and writing around a pretty demanding day job – coupled with the exigency of needing to earn a living – strung out the process. Luckily, I’ve been blessed with a very understanding and supportive publisher.

Books are at their best when they take on a life of their own; when one discovery leads on to another. It’s like finding the doorway in to the secret garden. Initially, I’d taken a far more chronological and strictly themed approach. There were going to be ‘art’ chapters; chapters that dealt with the witch in music and film; and chapters that set the witch within different strands of literature. In the end, the lines blurred and the individual stories – or test cases – surrounding figures like Isobel Gowdie, Urbain Grandier, Unora ‘the Witch of Prague’, or Ursula Kemp came to encompass all of those different strands.

In particular, I hadn’t expected the figure of the French historian, Jules Michelet (1798-1874) to come into such sharp focus. He is often dismissed out of hand by writers on witchcraft as being a rather hackneyed and peripheral figure, more interested in profits and fame than veracity: but the more that I read of his work the more I warmed to him and his ideas. I’m convinced that he is the seminal figure in the foundation of modern witchcraft, bridging the Enlightenment and Romantic movements. More than anyone else, he was able to scrape away the centuries of dirt and derision from the witch, and celebrate her as a progressive role model for women, as maiden, mother and crone – confident, knowing and sexual, as opposed to sexualised. Freed from her rags, the witch has never looked back.

Q 3. Do you think your Celtic ancestry contributed to the way you approached this subject and what personal insights did you gain when researching then writing the book?

The Celtic nations of Ireland and Wales can take pride as being areas where witches were not persecuted. The pattern is a little different in the Isle of Man, where there was the famous case of a mother and son – Margaret Ine Quayne and John Cubon – who were burned at the stake in Castletown in 1617. With one of the primary sources now lost and the surviving trial record terse and laconic, rather than revelatory, it is extremely difficult to establish what form their witchcraft took, or even if it was that – as opposed to a wider charge of treason – which occasioned their deaths. What is clear is that these deaths so traumatised and polarised island society that the local elites, from then on, actively colluded to ensure that capital punishment would never again be enacted for the crime of witchcraft.

Later, when Bishop Wilson’s evangelical fervour attempted to re-ignite witchcraft persecution, in the eighteenth century, Manx juries were incredibly reluctant to convict and were keen to effect a compromise between accuser and accused, employing a complex – and highly nuanced – system of public apologies and reconciliations, centring around the local kirk. In this way, when Mary Callow of Lonan parish – a possible relative! - was assaulted by her neighbours, who attempted to scratch her (drawing the blood of the witch in order to break the power of her spell); the rest of the family moved quickly to use the courts as a means of redress. It was the attack, rather than supposed witchcraft, that now concerned the authorities and it was the leader of the mob who had to apologise and do his penance on the kirk ‘naughty step’. It’s quite a verdict for Celts and Callows to be proud of!

Q 4. In your research and preparation did you find anything that you found particularly disturbing?

Witchcraft persecution is, by its very nature, disturbing. When you think that over the course of roughly 200 years, starting in the late fifteenth century, some 40,000 people – most of them women – were executed for being witches and an unknown number of additional victims were dealt a more random form of ‘justice’ by their neighbours, through common assaults, lynchings or duckings: it’s a tale of callous brutality, undertaken in the name of faith and probity.

In most cases, the use of judicial torture is the key to uncovering the ‘crime’. When confessions are not forcibly obtained – the accusations tend to dry up. It’s what separates the fate of Apuleius (the magician of the Roman world) from that of Urbain Grandier (a charismatic priest in Richelieu’s France). Both men run rings around their accusers in the court room, but the use of torture to extract confessions – banned in the Roman Empire but freely employed by seventeenth century European demonologists – effectively doomed Grandier, whose eloquence was drowned out by screams as his interrogators repeatedly shattered his shin bones.

Those, in our own age, who decry Aldous Huxley’s novelised account of his trial, or Ken Russell’s film version of The Devils, as ‘obscene’ would do well to think about the true obscenity of witchcraft trials which depended upon the progressive dehumanization, torture, and public execution of the accused.

Q 5. What would you like people to gain from the information you have presented in Embracing the Darkness - A Cultural History of Witchcraft?

I’d like them to think about the creative tension that exists between the much-maligned legacy of the European Enlightenment (which effectively brought the trials to an end) and the romantic anti-rationalism of much of today’s New Age movement. Disbelief in witchcraft, at an elite and judicial level, actually enabled the ideas and the themes that would prove instrumental to the reconfiguring of the witch as a liberating female archetype for the revived Pagan and new feminist movements to flourish.

It’s not reason but, as Goya understood so well, the sleep of reason that produces the monsters.

Q 6. Finally - What project are you currently working on?

In the short term, I’m finishing an article upon fairy tales and their writers in East Germany during the Cold War; and the manner in which these stories were anything but grey, concrete and formulaic. Over a longer period, I’m pleased to say that a grant from Culture Vannin and a contract from Helion Books will bring me back to the Isle of Man to work on James Stanley – ‘Yn Stanlagh Mooar’ / the ‘Great Stanley’ – as Cavalier and Lord of the Isle. It sounds like just another example of ‘top down’ history; but it is conceived as a means of exploring the survival of Gaelic culture and language upon Man at a time of enormous change and military threat. Expect the Manx to take centre stage together with the celebration of a small nation which survived, and even flourished, against all the odds.

"Embracing the Darkness - A Cultural History of Witchcraft”, by John Callow, is available to purchase from Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk - if you purchase through these links, you will be helping support this site and its work to promote Celtic cultural identify.

- Pan-Celtic

- English