Remarkable Story Of The Imprisoned Lady of St Kilda

Kidnapped and imprisoned on a remote and lonely Scottish island the story of Rachel Chiesley, or Lady Grange (1679–1745) as she was known is a remarkable one. It takes us back to the dangerous period of the Jacobite risings when those that sought the restoration of the Stuart monarchs to the throne took arms against the British government on a number of occasions between 1688 and 1746. A cause to which the Gaelic-speaking Scottish Highland clans were linked and one whose defeat resulted in misery, persecution and would ultimately have a devastating impact upon Gaelic culture and clan society in the Highlands of Scotland.

Rachel Chiesley was one of ten children born to John Chiesley and Margaret Nicholson. Her father was convicted and hanged for the murder of George Lockhart, Lord President of the Court of Session, who was murdered in Edinburgh on 31 March 1689. Rachel Chiesley was described as very beautiful and in about 1707 married James Erskine (1679 – 20 January 1754), who took the title Lord Grange and was the younger son of Charles Erskine, Earl of Mar. Her husband was a lawyer, who became Lord Justice Clerk in 1710. The marriage produced nine children but then descended into trouble, partly it seems due to his infidelity. The bad relationship that developed between them eventually became public knowledge and led to the remarkable events that saw her abduction and banishment to the remote Scottish islands where she would end her days.

It is thought by many that the kidnapping and incarceration of Lady Grange was linked to the bitter separation that had taken place from her husband. Lady Grange produced letters that she claimed were evidence of his Jacobite sympathies and could have proven his involvement in plots seen as treason against the Hanoverian government in London. The situation of such accusations would have proven dangerous for him. His brother, John Erskine, Earl of Mar (1675 - May 1732) had been exiled for his support for the Jacobites after the Battle of Sherramuir in 1715. It was also said that Lady Grange had a strong and outspoken character who was angry at her husband’s infidelity. Perhaps 18th-century attitudes to women and her willingness to speak out and fight for her rights played a part in her demise.

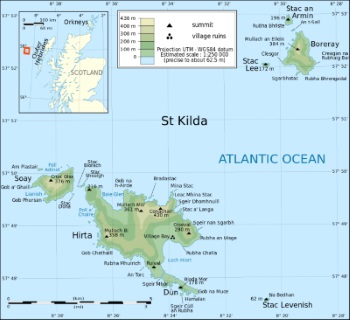

On the night of 22 January 1732 a number of Highlander’s abducted Lady Grange from her Edinburgh home at the instigation of her husband. Lady Grange was taken to the island of Heskeir (Scottish Gaelic: Eilean Heisgeir) part of an island group west of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. After two years she was moved to St Kilda (Scottish Gaelic: Hiort) an isolated archipelago and the westernmost islands of the Outer Hebrides. Here she stayed on Hirta (Scottish Gaelic: Hiort) which is the largest of that island group. She lived in a cleit, a primitive hut made from dry stone walls with stone roof slabs capped with turf. Lady Grange was thought to have been moved from St Kilda in 1740, but not before she had written two letters that were smuggled out and relayed her story of kidnap and imprisonment.

Lady Grange eventually ended up in Skye ( Scottish Gaelic: An t-Eilean Sgitheanach or Eilean a' Cheò) where she would die on 12 May 1745. Trumpan churchyard on Skye is the burial ground of Rachel Chiesley, Lady Grange. Here ends the story of the Prisoner of St Kilda whose husband had her kidnapped and incarcerated on various Hebridean islands for nearly ten years. Where she lived a solitary life amongst the Gaelic speaking community and is said to have walked by the sea lamenting her loss of freedom and enforced isolation. However, her story lives on in speculations about the motives for her abduction, as well as in literature and the arts that has inspired poetry, plays and a novel. Scottish poet and translator Edwin George Morgan (27 April 1920 – 17 August 2010) wrote this poem 'Lady Grange on St Kilda' from Sonnets from Scotland 1984:

They say I'm mad, but who would not be mad

on Hirta, when the winter raves along

the bay and howls through my stone hut, so strong

they thought I was and so I am, so bad

they thought I was and beat me black and blue

and banished me, my mouth of bloody teeth

and banished me to live and cry beneath

the shriek of sea-birds, and eight children too

we had, my lord, though I know what you are,

sleekit Jacobite, showed you up, you bitch,

and screamed outside your close at Niddry's Wynd,

until you set your men on me, and far

I went from every friend and solace, which

was cruel, out of mind, out of my mind.

- Scottish

- English

- Log in to post comments