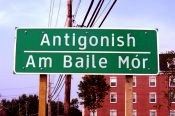

Nova Scotia: The Edge of the Celtic World

To celebrate Gaelic Awareness Month 2016 in Nova Scotia, we are re-featuring this article originally published on September 11, 2013.

In the 1800s the Scots Gaelic community of Nova Scotia is estimated to have exceeded 100,000 Gaelic speakers.

The 18th century witnessed upheaval in the centuries old way of life in the Scottish Highlands and Islands of Scotland. The events following the Scottish rebellion against the British Crown in 1745 caused a disruption in the long standing relationship between the residents and the owners of the Land. The complex history of land ownership in the Highlands and Islands saw landlords, heirs to ancient Clan Chieftainships and in many cases newly ennobled by the British Crown, gradually become estranged from the residents of the land. Economic advantage was to be gained from the removal of the residents so as to facilitate modern farming techniques. Tragic scenes of displacement and eviction followed and led to the betrayed Gaelic speaking residents becoming homeless refugees in their ancestral homeland.

These events led to emigration from Scotland to the new worlds. One of the destinations of the refugees was the Maritime of Canada. Cape Breton, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia was a primary destination:

Between 1817 and 1838 alone, the population in Cape Breton grew from approximately 7,000 people to 38,000 people. Almost all these people were Gaelic speaking Scots from the Western Highlands and Islands of Scotland.

The new immigrants established settlements in Cape Breton and there quickly developed a thriving Scots Gaelic culture. According to the Nova Scotia Provincial Office of Gaelic Affairs website:

Within each of these settlements, the Gaelic speaking people usually preserved the particular dialect of Gaelic that they brought with them from the old country, such that whenever they would move away from their own locality they would hear a different dialect of Gaelic. Sometimes the dialect would be so different from their own that they would have difficulty in understanding it correctly.

James MacKillop, in his 2005 “Myths and Legends of the Celts”, describes the depth and complexity of the of Gaelic speaking culture of Cape Breton:

The furthest flung, newest and least studied canton of the Celtic world lies in the Canadian Maritime province of Nova Scotia. Large numbers of impoverished, landless Gaelic-speaking Highlanders were settled there from the late eighteenth century through to the middle of the nineteenth. Some were victims of the Clearances. Whereas Irish, Welsh and Scottish Gaelic were once spoken, written and published elsewhere in North America, only in Nova Scotia did a widespread oral tradition flourish, one that has persisted until the twenty first century. The 1900 census recorded 100,000 speakers, most of them born in the province. This Gaidhealtachd [Gaelic Speaking Region] encompassed most of Cape Breton Island.

MacKillop continues as he describes the unique nature of Cape Breton culture in what he refers to as a land of herring fisheries and maple trees:

Some of the traditions that migrated to Nova Scotia, however, are not recorded in Scotland. Their existence supports the documentable pattern that archaic survivals are found at the periphery of a given cultural area.

In 1850 the Scots Gaelic community of Nova Scotia is estimated by some to have exceeded 100, 000 Gaelic speakers. The malign neglect of the Provincial and Canadian governments failed to give Gaelic the same rights and recognition as that afforded English. It was the de facto policy of assimilation which was lethally effective against the Scottish language. For example, Gaelic was never the language of instruction in the Cape Breton school system despite the significant presence of the Gaelic speaking community. The result has been the steady decline of the language. By 1930, just 80 years after the 1850 census showed over 100,000 speakers, the number of Gaelic users in Nova Scotia had fallen to just 30,000.

The Atlantic Gaelic Academy, founded in 2007, is one of the institutions in the forefront of efforts to revitalize the Gaelic language and culture of Cape Breton. The Academy boasts a full curriculum of Gaelic language instruction and uses its own unique program and method of instruction. The following is a quote from the Academy’s web page

Its TILLStm method (Total Integrated Language Learning System) was developed and perfected over a five-year period in a regular on-going class environment, and it has proven to be highly successful. It makes it much easier and quicker to learn a new language. There is an emphasis on conversation and an average of approximately 75% of class time is spent speaking Gaelic, with sufficient time also spent learning proper sentence construction and vocabulary.

The Academy President, John Alick MacPherson, is a native Gaelic speaker from Harris and North Uist, Scotland and former Chairman of the Scottish Government task force whose findings led to the Gaelic Language Act. The Gaelic Language Act is now being implemented in Scotland.

Interview with Executive Director of The Atlantic Gaelic Academy, Mr. Robert Leonard

Transceltic interviewed the executive Director of the Academy, Mr. Robert Leonard, who painted a somber yet optimistic picture of the future state of the Gaelic tongue in Cape Breton. When asked for his assessment of the future of the language, Leonard responded:

It is not all that bright. Action has to be taken to reverse the trend of the past to stem the decline.

Leonard pointed out that the purpose in establishing the Academy was recognition of the need to take action. Leonard pointed out that there no longer exists what one could call “Gaelic Speaking Communities” in Cape Breton but detects an upsurge in interest in the Gaelic culture and language and cited the growing use of technology and social media, such as Twitter, in promoting the usage of the tongue. The role of arts and popular music as factors in the revitalization of the language was also cited by Leonard:

I think music, particularly Celtic Music, plays a favorable and significant role in cultural awareness and reminds people of their roots, their Scottish identity. Artists and singers are held up as role models and in so much as they use the language in the music, and the music is viewed as being connected to the language, this cannot but have a positive impact.

Guarded optimism for the future of the language and culture of Gaelic Nova Scotia is also a theme of the landmark study published in 2002 by the Nova Scotia Museum which is entitled “Gaelic Nova Scotia – An Economic, Cultural and Social Impact Study” (Curatorial Report #97) , written by Michael Kennedy. A commanding work of over 300 pages which surveys the historical context of Scottish immigration to Nova Scotia and the Gaelic institutions in Nova Scotia working to preserve and promote the Celtic tongue and culture of the province at the time of publication. In addition, Kennedy’s work goes into an expansive analysis of the unique Gaelic music and dance of the province and ends with an outline of a practical plan for the revitalization of the culture and the language. This impressive survey makes the following observation:

Nova Scotia is home to the last Gaelic speaking communities in the New World. The nature of migration from Scotland ensured that large, nearly homogeneous communities were established here, dominating nearly a third of the province’s area. Within that richly Gaelic environment developed a true Canadian and North American Gaelic community that is now unique in the world. Generations of undiluted cultural transmission went hand in hand with generations of adaptation and creativity in the New World environment.

After noting the gradual decline of Gaelic culture and language, Kennedy optimistically continues:

In recent decades, attitudes have changed concerning linguistic and cultural diversity (In Canada). Better education has begun exploding many of the myths that have been used to marginalize minority cultures, and there seems to be increased interest in Gaelic language both in Nova Scotia and internationally. The fact that cultural diversity is now prized and considered a tourism asset and economic development tool will be useful in any attempts to improve the future of Gaelic.

Transceltic's take

The state of Gaelic culture and language in Nova Scotia, given its precipitous decline from a thriving Celtic Nation of over 100,000 Gaelic speakers in the 1800s, combined with growing efforts to revitalize culture and tongue, can serve as a marker in our efforts to preserve, protect and promote the Celtic culture of the Six Nations and Nova Scotia.

We at Transceltic salute the efforts of the Atlantic Gaelic Academy, Michael Kennedy and the Museum of Nova Scotia.

Links

museum.gov.ns.ca/site-museum/media/museum/Gaelic-Report(1).pdf

Myths and Legends of the Celts

Get your copy from Amazon.com (US$) or Amazon.co.uk (GB£):

- Scottish

- English

- Log in to post comments