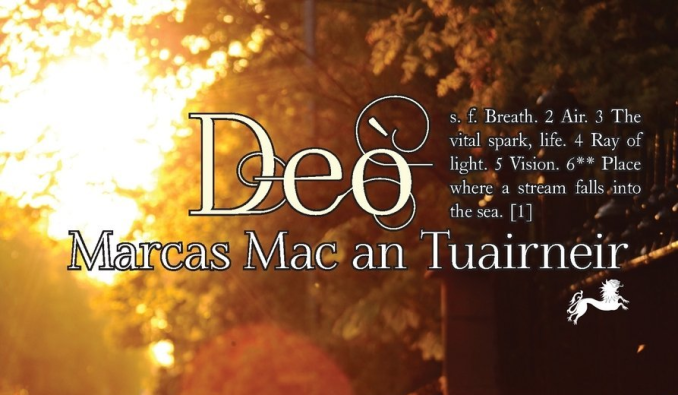

Interview with Marcas Mac an Tuairneir, Scottish Gaelic Poet, Author of Groundbreaking Poetry Collection "Deò" - Bringing Gay Themes to Scottish Gaelic Literature

Deò is a collection of poems written in both Scottish Gaelic and English by Marcas Mac an Tuairneir. In his poetry Marcas touches on Gay subject matter not often addressed in Gaelic writing. His work is refreshingly honest, using Gaelic in a way that reflects it as a living language that as such needs to continue to adapt and grow in the years to come. Marcas Mac an Tuairneir explores issues of sexuality that are personal to him, but also need to find a voice in modern Gaelic literature and poetry. His poetry is powerful and beautifully written.

Born in England, Marcas attended Kings College, University of Aberdeen in Scotland, where he graduated in 2008 with an MA Hons in Gaelic and Hispanic Studies and an MLitt in Irish and Scottish Studies in 2010. Moving to Glasgow in 2011 he gained an MA in TV Fiction, with the support of MG Alba, at Glasgow Caledonian University. Deò is his first collection of poetry and was written with the support of the Gaelic Books Council and has been widely acclaimed. Marcas is currently working on a second collection of poetry, as well as two novels and a TV drama script. We are therefore delighted that Marcas has taken time out of his busy schedule to talk to Transceltic.

Interview with Marcas Mac an Tuairneir

1. Your book of poetry Deò was written in Scottish Gaelic. What inspired you to write in that language?

I studied Gaelic and Hispanic Studies the first time round at Aberdeen University. It was interesting to learn minority and majority languages simultaneously and to investigate the interaction between their various cultures. Whereas the Spanish classes were quite large, the Gaelic classes were much smaller and I felt very at home in the department. It was a really inclusive, almost holistic, environment and it became clear that we weren’t being trained up to be merely competent linguists, but to be ambassadors for the community and culture. I suppose I felt, for the first time in my life, that I had a cause to espouse. Whilst I found socio-linguistics and language policy and planning to be interesting, my passion was always for the arts and literature in general. The majority of my academic research was about emergent voices in Gaelic poetry and it was when I was doing work experience at Sabhal Mòr Ostaig towards the end of my undergraduate degree that I first put pen to paper in Gaelic and wrote my first poems. I felt that I had to use the talents that I’d been blessed with to add to the canon instead of just analysing it.

2. The six Celtic languages of Cornwall, Ireland, Brittany, Isle of Man, Wales and Scotland are undergoing a significant renaissance both in their homelands and abroad at this time. What do you put this revival in fortunes down to?

I can’t claim to be an expert in the minutiae of the various linguistic struggles outside Scotland, although there is a lot of parity and the same images and concerns do turn up in a lot of the Celtic arts. I’m currently working for Bòrd na Gàidhlig in the communications team and it’s really exciting to see the benefit that the various groups and initiatives get from the funding ear-marked by the Scottish Executive, following the Language Act of 2005. Obviously, in Scotland the act and the foundation of Bòrd na Gàidhlig has been the most significant piece of legislature to strengthen Gaelic in the country, but we shouldn’t forget that the Gaelic cause has been a grass-roots movement for decades and many groups and individuals have given their time and expertise, often for little returns, in order to preserve and celebrate Gaelic and her culture. The Gaelic arts scene at the moment is incredibly vibrant and there is a lot of exciting work being done which really questions the status quo and how we identify as Gaels ourselves. It’s also an incredibly generous scene and I think that the fact that it is a minority community has a lot to do with how supportive artists are of their fellow artists. It’s not half as cut-throat or competitive as it is in a majority language arts context.

3. Deò was very well received. What do you think writing in Gaelic added to the work and were you pleased with the positive response that the book had?

It’s massively flattering to receive praise for your work, especially when it deals with such personal themes. I was incredibly lucky to have the support of Rosemary Ward and the Gaelic Books Council and my mentor Martin MacIntyre. I was also lucky that the current Gaelic poet laureate, Lewis MacKinnon, reviewed the book for the back cover. Gonazlo Mazzei and Margaret Bennett, my publishers at Grace Note, afforded me a lot of personal freedom with the book and allowed me the space to develop my own voice. Visually, the book, as an object, is unlike any other Gaelic poetry book and that is due to my collaboration with the illustrators Iain Ross and David Ramsay and Gonzalo who designed the layout.

In terms of language choice, there is a lot of debate about whether Gaelic poetry should be presented with translations vers-recto and whether this has a positive or negative impact on the readership. Fundamentally, this wasn’t my major concern, although I was certain that with this being my début collection, I wanted it to be my own voice completely and so I translated my own work. At the end of the day, Gaelic is my second language. I was born in England. I identify with both languages strongly, but in different ways. Gonzalo’s advice was to present the works through translation, firstly to take the works out to a wider audience and to facilitate readers who are less confident in the language so that they can refer to the translation if need be.

Ultimately, this is a Gaelic poetry collection and that is significant. Gaelic’s vocabulary is a gift to anyone writing in the language because it is so rich and diverse. It is a rhythmic, onomatopoeic language and this is why it has such a strong poetry and song tradition. I guess for me it’s like an artist choosing his palette, Gaelic’s hues and textures are different, but they are very exciting to use.

4. What made you choose the subject matter and the title of your book?

I found the title when browsing Dwelly’s dictionary one day. I just thought it summed the book up perfectly. The word means various things which are all semantically linked and of course the metaphor of breathing is the overriding metaphor running through the collection. I play with it in various ways, but essentially it’s about drawing the outside world inside you, making it part of you and then putting your own creativity out.

I don’t feel that I selected any kind of subject matter for the book. I never really intended it to be a book when I started writing. I just wrote because I wanted to, or at times, had to. It enabled me to understand my own emotions and experiences. I wrote about my life as it was at the time. I was studying, moving around the country and even living abroad, so culturally the subject matter is quite expansive, but because I was going through such a process of self-awareness and transformation it’s also extremely personal. One critic called it ‘raw’, another called it ‘self conscious and almost self indulgent.’ I agree with the positive and the negative. It is my first collection and was written by a twenty-something. The works I’m writing now are markedly different, but I hope I have retained the sense of abandon and the honesty.

5. In your book you write about the loss of the boat Iolaire which went down off Leòdhas (Lewis) in the Na h-Eileanan Siar (Outer Hebrides) on New Year’s Day 1919. Why did you choose to write about that particular incident?

The songs were an interesting part of the process. I was presented with the opportunity to co-write for a friend’s album and was given the songs in crib form with recordings of the melody. The subject matter wasn’t my own choosing at all – traditional themes and stories, at that point, weren’t my thing at all – but it was exciting to find a new way to be creative within the boundaries set by someone else. I stayed away from stories which are so intrinsically Hebridean, because I am not from that community and I felt it would be almost intrusive to touch them. But when the commission came, I felt a sense of freedom and luckily the final outcome was a positive one.

6. How has the success of the book impacted on your life and work?

The book has opened the door for me in a big way. I have been invited to read at several events and have a busy schedule right up until the end of the year with festivals and appearances. Its led to several commissions in other genres including writing for TV, the stage and my début novel, which will be published by Acair. I’ve applied to do PhD at the University of Edinburgh in Creative Writing and Gaelic and am currently looking for support in funding that. I don’t think I would have had the courage to go back into academia without ‘Deò’ being under my belt. It was such an affirmation seeing it in print and now it’s out there, I can hold it in my hands and say ‘yes, you can do this. You are a writer.’ The aim now is just to build on what I’ve started. Keep developing and exploring new forms and subjects. The floodgate is well and truly open now.

Transceltic thanks Marcas Mac an Tuairneir, a gay writer bringing new themes into Scottish Gaelic literature and a welcome addition to the vibrant Gaelic arts scene.

Deò is available from Amazon.com (US$) or Amazon.co.uk (GB£):

- Scottish

- English

- Log in to post comments