The Deliberate Repression of the Celtic Languages

There are only six Celtic languages spoken in the world today: Breton, Cornish, Scottish Gaelic, Irish, Manx and Welsh. For centuries there has been a systematic campaign to destroy the native languages of the Celtic lands. The use of these languages was banned in schools and work places by brutal means in Alba (Scotland), Breizh (Brittany), Cymru (Wales), Éire (Ireland), Kernow (Cornwall) and Mannin (Isle of Man).

This has been undertaken as part of a combination of colonialism and greater English, or in the case of Brittany, French centralisation and nationalism. A reminder of this campaign is set out in this quote from the Blue Books 1847 - a British Government report on Education in Wales. The report was met with outrage in Wales because of the arrogant remarks of the three non-Welsh speaking Anglican commissioners regarding the Welsh language:

"The Welsh language is a vast drawback to Wales, and a manifold barrier to the moral progress and commercial prosperity of the people. It is not easy to over-estimate its evil effect...it disserves the people from intercourse which would greatly advance their civilisation, and bars the access of improving the knowledge of their minds. As a proof of this, there is no Welsh literature worthy of the name."

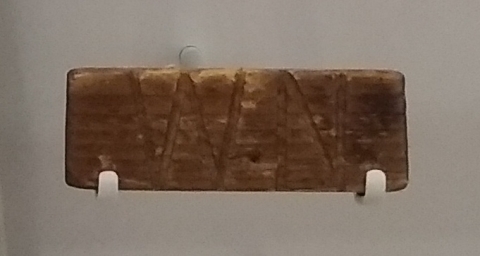

This report and the attitudes of those that thought in this way resulted in the repression of the Welsh language. Not least the "Welsh Not" used by teachers at many schools in Wales in the 19th century to discourage children from speaking Welsh. This took the form of a dreadful piece of wood hung around a child's neck for the whole day if they were caught speaking Welsh at school.

This campaign to eradicate the Celtic languages took place in a numbers of forms throughout all of the countries where a it was spoken. In the case of Brittany it was demonstrated at the time of the French revolution when AbbéGregoire (1794) in his report on the necessity of universalising the French language, wrote that: "…..Breton and Basque, represent the barbarism of centuries past and need to be obliterated and replaced by standard French."

This view persisted through to the French Minister of Education’s statement of intent in 1925 that: "For the linguistic unity of France, the Breton language must disappear." Onwards to the offensive official warning signs that appeared in schools in the 1950s declaring: "No spitting on the ground or speaking Breton." Echoing the 1925 statement in 1972, George Pompidou, who was President of France at the time, said that there was no place for regional languages in France. This attitude toward the Breton language persists today with many continuing attempts to undermine teaching in the Breton language by the French state.

The Celtic languages in the six nations where they are spoken have survived, but in places and at times came close to extinction. It is recognised that language is intrinsic to the expression of culture. It is the means by which culture and its traditions and shared values may be conveyed and preserved. There is a need to continue to promote and save endangered languages and the concerted efforts being made to do this in the six Celtic nations is meeting with success. There are also groups of speakers and learners throughout the world, often the descendants of those who left their Celtic homelands many years ago. It is important to join in the effort to save and promote these languages wherever you are.

Image: Welsh Not on display at St Fagans National Museum of History. In 1852 itwas used at Pontgarreg School, Llangrannog.