Interview with Dr. Jenny Butler: The Celtic Folklore Traditions of Halloween

Originally published in 2013

The ancestry of modern Halloween, which needs no introduction here, leads on a straight line back to Samhain, the Celtic feast day of the Dead. One of the four annual feast days of the Celtic world, Samhain was such an important feast day that it did not escape the notice of Julius Caesar as he ravaged Celtic Gaul who remarked that the Celtic god of death and winter was worshipped on this day.

Samhain was the principal feast day of Celtic Ireland prior to the arrival of Christianity. Over time, the Christianisation of Celtic religious belief re-made Samhain into All Saints Day, a principal Holy Day of the Catholic Church, which as the name of the Holy Day suggests, gives a nod to its roots as the Celtic feast of the dead. The smooth transition from Celtic Samhain to the Christian holiday honouring dead Christian Saints is just another example of how expert were St. Patrick’s missionaries in weaving Celtic myth into Christian belief making it seem as if the new religion was really an extension of the existing faith in the Gods of the Celtic Pantheon.

Transceltic are honoured to have had the opportunity to interview Dr Jenny Butler on her insights into the origins of Halloween. Dr Butler is a folklorist based at University College Cork's Folklore and Ethnology Department with a PhD thesis on the topic of Irish Neo-Paganism. Dr Butler’s principal interests are in the areas of mythology, belief narratives, folk religion, ritual and festival. A member of The Irish Society for the Academic Study of Religions (ISASR), she has numerous articles to her credit. Dr Butler is currently working on a book about Irish contemporary Paganism.

1. What is the connection between the Celtic Feast Day of Samhain and Halloween?

Halloween is a festival that falls on October 31st, which possibly has its foundations in the Celtic festival of Samhain. In Irish Gaelic, Oíche Shamhna is the name for ‘Halloween Night’. Both feasts, Samhain and Halloween, are connected with the dead and take place on the same calendar date. In the Gaulish (Coligny) calendar, the Samonios festival began the pastoral year and the last evening of October was old year’s night. The word Samhain is derived from the Old Irish language for this festival and is still used in the modern Irish language to refer to the month of November. The word might be a linguistic inversion of the Irish-language term samhradh (summer) so that Samhain means ‘summer’s end’, from samh, ‘summer’ and fuin, ‘end’. Thus, Samhain was the festival that marked the ‘New Year’. This was a time of liminality (meaning a time of transition), danger and uncertainty, since it stood at the boundary between two halves of the Celtic year, i.e. summer and winter. It is thought that the Celtic festivals began on the eve of the specific day of celebration since the Celts measured their days from their dusks, and so Samhain celebrations began in the evening. Similarly with Halloween, celebrations begin on the eve of the feast, ‘eve’ being archaically spelled even or e’en; this is why you sometimes see it spelled as Hallowe’en.

2. As an academic specialising in folklore, what folkloric traditions connected to Samhain have survived into modern times to become part of Halloween?

The Celtic Samhain was a feast of the dead and it is likely that certain traditions connected to honouring and remembering the dead continued in folklore. Many customs have to do with the idea of the souls of the dead returning, as this is a time when it is believed that deceased relatives could come back to the place where they had once lived. The contemporary custom of placing lighted candles in hollowed-out pumpkins with features carved to look like eerie grinning heads is a continuation of the tradition of doing the same thing with a sugar beet or turnip, as pumpkins are not native to Ireland. Some have suggested that this custom was to do with lighting the way for the souls of the returning dead. In Irish folklore, the night of Samhain is when the barrier between the human world and the otherworld becomes thin, allowing the dead to come through and walk the Earth. People would leave their doors unlatched and leave food out for their dead relatives who might return to the house on this night.

In pre-Christian times, bonfires were lit on sacred hills and bonfires are also connected with pre-modern Irish Halloween customs and continue today but in a more regulated form. Traditionally in Ireland, bonfires are lit at Halloween and children go from house to house to collect items to burn in the bonfire. However, regulations were introduced in July 2009 to  strengthen laws against backyard and public waste disposal, including burning. Technically, anyone collecting waste materials apart from City or County Councils should have a ‘Waste Collection Permit and hefty fines can be imposed on those caught disposing of waste by burning. This has led to a decline in the tradition of going house to house to collect materials for the bonfire and in turn has resulted in fewer bonfires at Halloween. Some local authorities organise approved bonfire events but the nature of this is different to the tradition of collecting for, and spontaneously lighting a bonfire. Those with hearths in their houses light fires at Halloween, as around a fire is a traditional setting for storytelling sessions and the light and heat adds to the festival atmosphere.

strengthen laws against backyard and public waste disposal, including burning. Technically, anyone collecting waste materials apart from City or County Councils should have a ‘Waste Collection Permit and hefty fines can be imposed on those caught disposing of waste by burning. This has led to a decline in the tradition of going house to house to collect materials for the bonfire and in turn has resulted in fewer bonfires at Halloween. Some local authorities organise approved bonfire events but the nature of this is different to the tradition of collecting for, and spontaneously lighting a bonfire. Those with hearths in their houses light fires at Halloween, as around a fire is a traditional setting for storytelling sessions and the light and heat adds to the festival atmosphere.

Halloween traditionally involves divinatory customs. Due to the belief that this is a time when the symbolic door between the world of the dead and the world of the living is open, there is the idea that people may be privy to supernatural knowledge concerning the future, since the ordinary barriers of time and space are considered to be transparent. Many of these hoped-for glances into the future involved marriage on the horizon for an individual, usually a young woman. For example, young women would hang a garment to dry before the fire and watch from a corner of the room to see an apparition of their destined husband come down the chimney to turn the garment over so that the other side would dry. Irish people traditionally tell fortunes and attempt to foretell the future in the belief that they would be privy to supernatural aid or otherworldly knowledge at this time.

3. What are the origins of “Dressing Up” for Halloween?

One theory on the origins of guising and dressing as ghosts is that it has to do with the belief in the dead returning on this night and the change of appearance may protect the human from being recognised by the dead. The spirits wandering included what are known as ‘the unhappy dead’ so there was fear of past grievances or wrongs done by the living to the dead person while they had been alive. The atmosphere of Halloween has been described as ‘carnivalesque’ and the sense of things being topsy-turvy and inverted may have given rise to people having fun and using an opportunity to change their appearance into something they were not ordinarily. It is a playful time when it is acceptable to have a subversive appearance, so people can chose to dress as they wish, whether that is as something scary or outlandish.

4. What role did the Druids play in the observance of the ancient Feast Day?

We have relatively little information that specifically relates to the observance of Samhain in pre-Christian Ireland, but we can tell from mythology alone that it was a time of some importance. The druids feature prominently in Celtic mythology and are described as the priesthood of the Celts. We can surmise that the druids were involved in the ritual activities connected to Samhain. There was perhaps some ancient ritual practice connected to symbolically mourning the death of summer and marking the start of winter.  The end of one year and the transition into a new one is a liminal time, simultaneously sombre and joyful, rather like New Year’s Eve today. We know that bonfires are connected with the ancient feast of Samhain and there have been suggestions that the practice of lighting fires on the hills of Ireland was to symbolically mirror the light and colour of the sun in a ritual that perhaps was part of a sun-worshipping religion. Another theory is that the fire lighting rituals had some other celestial significance that has been lost to us. One of the sites associated with the observance of Samhain is the Hill of Ward or Tlachtga, located near Athboy in County Meath. This hill is 116 metres high with a prehistoric ringfort (a circular fortified settlement which dates back to the Iron Age) atop it. Legend has it that druids gathered there to light huge fires as a signal that Samhain festivities should commence. There is evidence that great fires were lit on this hill in pre-Christian times. Tlachtga is clearly visible from The Hill of Tara in County Meath, one of the most well known of Irish sacred sites, which was also a significant Samhain site in ancient times. The fire-lighting rituals on the hills were connected. There are references in medieval manuscripts to Feis Teamhrach or the Feast of Tara, which was said to take place three nights before and three nights after Samhain. Druids are also associated with Tara and the rituals that took place there.

The end of one year and the transition into a new one is a liminal time, simultaneously sombre and joyful, rather like New Year’s Eve today. We know that bonfires are connected with the ancient feast of Samhain and there have been suggestions that the practice of lighting fires on the hills of Ireland was to symbolically mirror the light and colour of the sun in a ritual that perhaps was part of a sun-worshipping religion. Another theory is that the fire lighting rituals had some other celestial significance that has been lost to us. One of the sites associated with the observance of Samhain is the Hill of Ward or Tlachtga, located near Athboy in County Meath. This hill is 116 metres high with a prehistoric ringfort (a circular fortified settlement which dates back to the Iron Age) atop it. Legend has it that druids gathered there to light huge fires as a signal that Samhain festivities should commence. There is evidence that great fires were lit on this hill in pre-Christian times. Tlachtga is clearly visible from The Hill of Tara in County Meath, one of the most well known of Irish sacred sites, which was also a significant Samhain site in ancient times. The fire-lighting rituals on the hills were connected. There are references in medieval manuscripts to Feis Teamhrach or the Feast of Tara, which was said to take place three nights before and three nights after Samhain. Druids are also associated with Tara and the rituals that took place there.

5. What role did fairy belief have at Samhain and do you see elements of the fairy belief surviving in the celebration of Halloween?

At Samhain, the fairy mounds called sidhe (also called ringforts, liosanna or ‘fairy forts’) are thought to open up so that the fairies (these supernatural beings as well as their habitations are called sidhe or sí in the Irish language; the word was translated into English as ‘fairy’) and other otherworldly creatures can pass into human dwellings and intermingle with humans. The traditional Irish beliefs about fairies include their conceptualisation as the human dead, or the idea that the human dead can be “in the fairies”, part of the otherworld or fairy realm. So, the beliefs about the fairies being in the vicinity of humans on this night and the dead returning could be one and the same.

6. Can you comment generally on the concept of the Otherworld in Celtic folklore?

The ‘otherworld’ is generally an academic term used to describe the Celtic spirit realm. In Celtic myth, in both Welsh and Irish mythologies, the otherworld is believed to be located either on an island or underneath the earth. In Irish, the otherworld is called Tír na nÓg or Land of Youth, also referred to as Tír Tairngire, Land of Promise. In this place, death and sickness do not exist. It was where the Tuatha Dé Danann, the ‘tribe of Anu’, the mythical people associated with the fairies of later folklore, settled when they left Ireland’s surface. Tír na nÓg is described as being underground or under the ocean and in folklore it is said to be accessible by certain special places on the landscape. These places include the fairy mounds or ‘fairy forts’. Particular caves are also believed to be entrances to the otherworld. These beliefs are comparable to various different cultural traditions around the world where the underworld or otherworld, the abode of deities or other supernatural entities, can be accessed via cave systems. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underworld and, perhaps because of their shape, many caves are believed to connect the human realm with the spiritual realm, which is conceptualised as outside of normal time and space. Caves are liminal sites in that they are spaces under the ground but also connect with the aboveground world so there is geographical continuity between world, but the liminality is not solely due the physical position; there are also symbolic interconnections between human and non-human realms. In Irish myth, Donn, a god of the dead, reigned over Tech Duinn (The House of Donn), which is described as being on or under Bull Island, located at the western end of the Beare Peninsula in the southwest of Ireland. In Irish myth, otherworldly locations are associated with magical apples and Emain Ablach, Old Irish for ‘fortress of apples,’ is said to be the true home of the sea god Manannán mac Lir. Interestingly, the Welsh otherworld is also associated with apples. Avalon is another name for the Welsh otherworld, Annwn, and its name suggests that it is an island of apples, from Old Welsh aballon, ‘apple’. The English word ‘Avalon’ derives from the Latin writings of Geoffrey of Monmouth in the twelfth century where he writes of Insula Avallonis, ‘Isle of Apples’ and in modern Welsh it is still known as Ynys Afallach, ‘Isle of Apples’.

7. How did the pagan feast day of Samhain become a holy day of the Catholic Church? Do you see a parallel in the merging of Imbolg, the feast day of the Celtic Goddess Brigit, into the Feast Day of the Catholic saint of the same name?

The pagan festival of Samhain did not directly morph into a Catholic holy day. In fact, All Saints Day was originally held on May 1st, but was moved to November 1st in the year 834 and the festival became fixed at November 1st on the Gregorian calendar. All Souls’ Day follows the day after All Saints’ Day. On November 2nd for All Souls’, Roman Catholics pray for the faithful departed souls who are in purgatory. ‘Halloween’ is etymologically related to the Christian festival of All Hallows Day, Hallowmas or All Saints’ Day on 1st November, as follows: ‘Hallows’ derives from the Old English word hālig, meaning ‘holy’. Hallow means ‘to make holy’ and before the year 1121 halgod (past participle) was used. Later, halwen and halowen (about 1300) were used and about the year 1745, the Scottish shortening of Allhallow-even (for All Hallow’s Eve) became Hallowe’en. It is likely that the holy days of All Saints and All Souls were placed near Samhain since it coincided with an already existing feast of the dead.

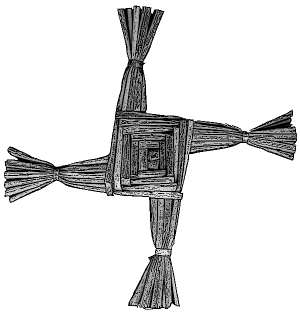

In relation to Imbolc and St Brigit’s Day, there is a clearer merging of pagan and Christian traditions. Brigit is a Christianised goddess who is associated with the spring festival. St Brigit’s feast day is February 1st and this is also the traditional marker of the beginning of spring. The Old Irish name for the festival is Oimelc, possibly meaning ‘ewe’s milk; lambs are born at this time of year and ewes come into milk at this point so that they will be able to feed the lambs during the coming season. The word imbolc or Imbolg, ‘im’ ‘bolg’, likely meaning ‘in the belly’, might also refer to lambing season. The Irish goddess Brigit is associated with human and animal lactation. She was said to be the daughter of the Dagda, one of the principle gods in the Celtic pantheon, and the wife of Bres, a half-Fomorii God. Although it is thought that people throughout Ireland venerated this goddess, she is particularly associated with the province of Leinster and she may have been the sovereignty goddess of that region. Her chief shrine was in Kildare, where priestesses tended her vigil fire. The shrine of Brigit was taken over by nuns and in legend these nuns continued to tend the sacred flame of Brigit at that same location in County Kildare until the thirteenth century, when the Bishop of Kildare decreed that the custom was pagan and therefore must cease. The goddess Brigit is a pan-Celtic deity and there are parallels in Britain with the worship of Brigantia, a name that means ‘high one’ or ‘queen’ and the name Brigit is thought by some scholars to be an epithet meaning ‘exalted one’. Another possible parallel is the Goddess Brigindo, worshipped by the Gauls. With the Christianisation of Ireland, the goddess Brigit became St Brigit and customs to do with the spring fertility festival were attached to St Brigit’s feast day in popular tradition. The correlation between Christian holy days and the earlier pagan religious festivals is even clearer in this case than in the case of Samhain.