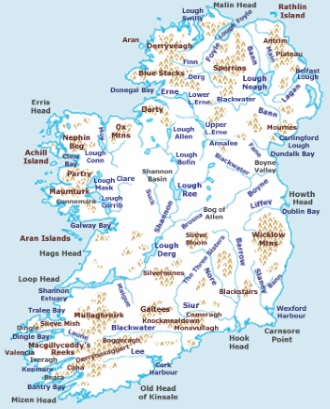

Magic and mystery of Ireland’s rivers

Ireland is a land rich in mythology and folklore. Reflected in the names of its lakes, rivers, valleys, glens and mountains. In Celtic lands it is not unusual to use the landscape as a mnemonic map. Geographical features hold a particular importance in Celtic peoples history, beliefs and culture. There is an understanding that we are part of and not separate from the land we inhabit. Consequently Celtic legends place the natural world at centre stage. In such stories things in nature can possess a spirit and presence of their own, including mountains, rocks, trees, rivers and all things of the land and the sea. Locations can be associated with a particular warrior, hero or deity. Each feature is linked to a story that stretches back beyond known history, passed on through oral tradition, some of which have subsequently been written down.

Amongst these geographical features, whether man-made, such as ancient mounds and standing stones, or naturally created features it is not unusual for some to be associated with the worship of pre-Christian deities. The aos sí or aes sídhe is an Irish term for a supernatural race that exist in Irish, Scottish and Manx mythology. Inhabiting an invisible world that coexists with the world of humans. They belong to the Otherworld (Aos Si) community whose world was reached through mists, hills, lakes, ponds, springs, loughs, wetland areas, caves, ancient burial sites, cairns and mounds.

In Irish mythology rivers and streams are often a boundary between this world and the Otherworld. Ireland's ancient rivers are steeped in tales about the ancient Gaelic gods of the Tuatha Dé Danann. The names of many rivers in Ireland, some of which are mentioned below, are testament to the enduring power of these ancient deities. After the period of Christian conversion in Ireland (from the fourth century AD onwards) the awareness of old pagan deities was not lost. It remained in the stories, traditions and folklore of the people and often merged into tales associated with important figures and saints linked with the arriving religion.

The sea, lakes, rivers, waterfalls and springs and the Celtic deities associated with them are testimony to the spiritual importance attached to water. Around the Celtic world treasures were often thrown into sacred lakes and rivers as offerings to the gods. Here is a selection of just some of the rivers in Ireland and the ancient stories attached to them, as well as a few that bear the names of the deities that created them.

River Bann (Irish: an Bhanna)

The River Bann is one of Ireland’s largest rivers and its name in Irish, An Bhanna, means ‘the goddess’, as is the case with The River Bandon (Abhainn na Bandan) in County Cork. The River Bann rises at Slieve Muck (Sliabh Muc) in the Mourne Mountains (na Beanna Boirche) in the north-east of Ireland. It flows into Lough Neagh (Loch nEathach), from which the Lower Bann then flows into the Atlantic Ocean at Portstewart (Port Stíobhaird). At the mouth of the Bann is Magilligan Strand (Trá mhic Giollagáin), a seven mile stretch of sandy beach. Close by is a sandbank, known as Ton’s Bank. There is a legend that a Storm God of the Tuatha Dé Danann is buried here. He later became associated with the Irish Sea-God, Manannán mac Lir. When the weather is stormy and the seas rough off the coast off Inishowen Head, there is a local saying that, ‘Manannán is angry today’.

The mouth of the River Bann is sometimes known as Inbher Glas and also Inbher Tuag. This is after Princess Tuag of Tara. Fostered by the High King Conaire, her beauty came to the attention of Manannán. He arranged for her to be placed under a sleeping spell and taken from Tara. After which she was carried to the mouth of the River Bann, and placed on Ton’s sand-bank in readiness for her departure to the land of Manannán (said to be the Isle of Man/Mannin). However, as she was still sleeping a great wave washed her out to sea and she was drowned.

River Barrow (Irish: An Bhearú)

The Barrow is the second longest river in Ireland behind the Shannon at 120 miles (192 km) long. One of which is known, along with the rivers Suir and Nore, as the Three Sisters (An Triúr Deirfiúr). It rises at Glenbarrow in the Slieve Bloom Mountains in Co. Laois and winds its way into Waterford Harbour in the south-east of Ireland. The earliest recorded name for the river is Berbha, from an 996 AD entry in the chronicles of medieval Irish history known as the Annals of the Four Masters. The name Berbha is believed to be associated with Borvo, the Celtic god of minerals and a healing deity linked with bubbling spring water.

River Blackwater or Munster Blackwater (Irish: An Abha Mhór or An Abhainn Mhór)

The River Blackwater is 105 miles (169 km) long and rises in the Mullaghareirk Mountains (Mullach an Radhairc). It flows easterly through Mallow (Magh Eala) and Fermoy (Mainistir Fhear Mai) in County Cork (Contae Chorcaí). Once in County Waterford (Contae Phort Láirge) it flows through Lismore (Lios Mór), then turns south at Cappoquin (Ceapach Choinn), finally spilling out into the Celtic Sea at Youghal (Eochaill) Harbour.

The route of the Blackwater takes it through areas steeped in ancient Irish history. The lands of the valley of the Munster Blackwater form the backdrop of the story recounted in the saga Forbhais Droma Dámhgháire. In which King Fiachu Muillethan, assisted by the powerful blind druid of Munster, Mug Ruith, repels an invasion of his kingdom by the famous High King of Ireland Cormac mac Airt.

Cormac had been trying to levy taxes from King Fiachu Muillethan of southern Munster. The druid Mug Ruith conducts a magical battle with Cormac's druids to help Fiachu. Mug Ruith has legendary powers. It is said he could grow to a great size, that his breath caused storms and turned men to stone. Wearing a hornless bull-hide and a bird mask, he flew in the roth rámach, a machine of enormous power. The magical weapons he had at his disposal included a chariot in which night became as light as day. He wielded a star-speckled black shield with a silver rim, and had a stone which when thrown into water could turn into a poisonous eel.

For all of his successful efforts in the defeat of Cormac, which some date to the 3rd century, Mug Ruith is given land from King Fiachu Muillethan. The territory Mug Ruith received for his descendants was Fir Maige Féne, later known as Fermoy.

The River Boyne (Irish: An Bhóinn or Abhainn na Bóinne)

The River Boyne (An Bhóinn or Abhainn na Bóinne) in Leinster, is about 70 miles (112 kilometres) long. The River Boyne is alleged to have its source at Trinity Well, Newberry Hall, near Carbury in County Kildare. It flows towards the Northeast through County Meath to reach the Irish Sea between Mornington, County Meath, and Baltray, County Louth. Legend associates the Well that is the source of the Boyne with the mythical King Neachtain of Leinster, and its water was reputed to have magical powers that gave wisdom. It is one of a number of Wells in Ireland that is sometimes known as Connla's Well or the Well of Segais. The River Boyne's name is derived from the Irish queen and goddess Bóann.

Boann created the Boyne after she went to the magical Well to taste the water. She also challenged the power of the Well by reciting incantations while walking anti-clockwise around it. The spring then rose in enormous waves and pursued her until she was swept into the Irish Sea and drowned. Boann, as well as being the goddess of the River Boyne, is according to the Lebor Gabála Érenn and Tain Bo Fraech, the sister of Befind and daughter of Delbáeth, son of Elada, of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Her husband is variously Nechtan, Elcmar or Nuada Airgetlám. With her lover the Dagda (Meaning 'The Good God') who was an important father-figure and chieftain of theTuatha Dé Danann, Boann is said to have bore Aengus. He is thought to have been a god of love, youth and poetic inspiration.

The River Boyne is a waterway of historical, archaeological and remarkable mythical heritage. Flowing as it does through the Boyne Valley, past the Hill of Tara (the ancient capital of the High King of Ireland), Navan, Ardmulchan, the Hill of Slane, the ancient temples at Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth, Mellifont Abbey, and the medieval city of Drogheda.

The River Corrib (Irish: Abhainn na Gaillimhe)

The River Corrib flows from Lough Corrib (Loch Coirib) through Galway to Galway Bay. Legend has it that the river was called after Gaillimh inion Breasail, the daughter of a Fir Bolg chieftain who drowned in the river. It is thought she was a tribal or local goddess of the river. Galway takes its name Gaillimh from the river. In medieval Irish myth, the Fir Bolg were a people in Ireland who were defeated by the Tuatha Dé Danann.

The River Erne (Irish: Abhainn na hÉirne or An Éirne)

The River Erne in the northwest of Ireland, is the second-longest river in Ulster. It rises on the east of Slieve Glah mountain in County Cavan (Contae an Chabháin). It flows for a length of about 80 miles (129 km) through Lough Gowna (Loch Gamhna), Lough Oughter (Loch Uachtair) and Upper and Lower Lough Erne (Loch Éirne), County Fermanagh (Fear Manach), to the sea at Ballyshannon, County Donegal (Béal Átha Seanaidh, Contae Dhún na nGall).

The River Erne takes its name from a mythical princess and goddess of a tribe of people called the Érainn. It is thought that her name Érann also gives Lough Erne (Loch Éirne) its name. In Irish mythology and folklore, there are a number of tales about the origin of the lake. One is that it is named after Erne, Queen Méabh's lady-in-waiting at Cruachan. Queen Méabh is queen of Connacht in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology. Erne and her maidens were said to have been frightened away from Cruachan when a fearsome giant emerged from the cave of Oweynagat. They fled northward and drowned in a river or lake, their bodies dissolving to become Lough Erne.

River Foyle (Irish: an Feabhal)

The River Foyle in the north-west of Ireland is a total of 80 miles (129 km) long. which flows from the confluence of the rivers Finn (Abhainn na Finne) and Mourne (An Mughdhorn) through the towns of Lifford, County Donegal (Leifear, Contae Dhún na nGall) and Strabane, County Tyrone (An Srath Bán, Tír Eoghain). It then flows to the city of Derry (Irish: Doire), into Lough Foyle (Loch Feabhail) and out to the Atlantic Ocean.

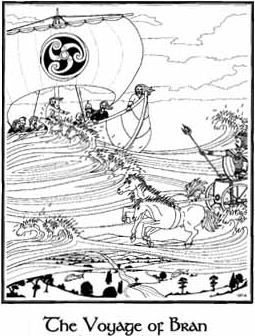

The Irish name An Feabhal refers to Febail, father of Bran. Bran mac Febail was out walking when he heard beautiful music. It lulled him to sleep and when he awoke he saw a silver branch with white blossoms in front of him. He returned with the branch to his royal house upon which a woman from the Otherworld appeared. She sings to him a poem about the land where the branch had grown.

In this magical Otherworld, it is always summer, food and water is plentiful, no sickness or despair exists, the people are happy, and there is no conflict. She tells Bran to voyage to the Land of Women across the sea. This he does the next day with a company of nine men.

Two days into his journey he encounters a man on a chariot. The man is the legendary Celtic sea god Manannán mac Lir. He tells Bran that he is not sailing upon the ocean, but upon a flowery plain and that there are many men riding in chariots, but that they are invisible. He reveals to Bran how he is to beget his son in Ireland, and that his son will become a great warrior. After this Manannán makes a prophesy about the boy and that Manannán mac Lir will be a teacher and a father to him.

Bran takes his leave from Manannán and arrives at the Isle of Joy. However, the people of the island do not respond to his calls and only laugh and stare at him. Bran responds by sending a man ashore to find out what is the matter. However, when the man sets foot on the island he behaves in exactly the same way as the inhabitants. Bran leaves him there and continues his journey.

He reaches the Land of Women, but is reluctant to disembark. At which point the leader of the women throws a magical cord to him which sticks to his hand. She then pulls the boat to shore, and each man paired off with a woman, Bran with the leader. After what seemed to them about a year, but it was actually many years, they remained happily until Nechtan Mac Collbran felt the need to return to Ireland. The leader of the women told them they would regret their decision and warns them not to step upon the shores of Ireland upon their return. They sail back to Ireland, but the people that have gathered on the shores to meet him do not recognize the name of Bran except in their ancient legends. Nechtan Mac Collbran jumps off the boat onto the land. So ancient is he his body immediately turns to ashes.

Bran tells the story of his voyage to the people of Ireland. He wrote it using the poetic tradition of quatrains in Ogham, the alphabet used to write the early Irish language. He then bade farewell to the people of his native land and set sail across the sea and was never seen again.

River Greese or Griise (Irish: An Ghrís)

The River Greesse is a tributory of the River Barrow in south-east, Ireland, and separates the counties of Kildare ( Contae Chill Dara) and Wicklow (Contae Chill Mhantáin). Close to the river is Killeen Cormac which had the earlier name, capella de Gris ("Gris Chapel"), quoted in the Crede Mihi, an ancient register of the Archbishops of Dublin, which gave its name to the river.

Killeen Cormac is an early ecclesiastical site and was used as a pagan burial ground before the introduction of Christianity to Ireland. There is a pillar stone here on which there is a mark of a hound's paw. Local legend tells that this stone marks the grave of Cormac, King of Munster. Cormac mac Cuilennáin (died 13 September 908) was an Irish bishop and was king of Munster from 902 until his death at the Battle of Bellaghmoon. After his death he was thought of as a saintly figure, his feast day being September 14th.

In local tradition it is said that Cormac's body was taken to the cemetery by a team of bullocks. When they reached the ‘Doon' of Ballynure the bullocks were thirsty. They pawed the ground, from which emerged water. After drinking the water, they travelled on until they reached Bullock Hill opposite to the cemetery. They stopped there and refused to go further and this was seen as a sign that Killeen was to be the last resting place for Cormac. The team of bullocks having left the body for burial travelled back across the marsh between the cemetery and Bullock Hill. While crossing the Griese they were swept away and lost. Another story is that there was a hound with the bullocks and body. On reaching Bullock Hill, the hound jumped across the river to the cemetery. He impressed the mark of his paw on top of the pillar stone, thus indicating where Cormac was to be laid.

River Inny (Irish: An Eithne)

The River Inny is a river within the Shannon River Basin in Ireland and is 40 miles (64 km) in length. Beginning at Patrickstown hill in County Meath (Contae na Mi) it enters Lough Sheelin (Loch Síodh Linn) in County Cavan (Contae an Chabháin). It then makes its way to Lough Kinale (Irish: Loch Cinnéile) on the borders of Counties Longford, Westmeath and Cavan. The river flows onwards into Lough Derravaragh (Loch Dairbhreach). As the river winds its way it goes near to Tenelick where the mythological Irish Princess Eithne (Ethniu) drowned in the rapids. She gave her name to the river. It flows westwards into Lough Ree (Loch Rí) before becoming part of the River Shannon (Abha na Sionainne), travelling through Athlone (Baile Átha Luain) to enter the Atlantic Ocean.

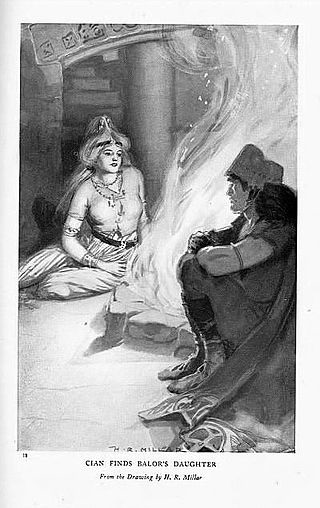

In Irish mythology Ethniu is the daughter of the Fomorian leader Balor, and the mother of Lugh. The fomorians are a group of supernatural beings and Balor was their king, described as a giant with an eye in the middle of his forehead. He was a formidable ruler and said to have the power to wreak destruction. There are different myths associated with Ethniu. One is that Balor, her father, hears a prophesy that he would be killed by his grandson. So to prevent this from happening and his daughter from having children he locks her in a tower on the island of Toraigh. Cian the son of Dian Cecht of the Tuatha Dé Danann, found his way into the tower and impregnated her. She gave birth to Lugh, who was then raised by the Fir Bolg queen Tailtiu and the sea god Manannán.

Lugh eventually becomes king of the Tuatha Dé Danann. The prophesy told to Balor that he would be killed by his grandson comes to pass. Lugh leads the Tuath Dé in the second Battle of Mag Tuired against the Fomorians, who are led by Balor. Lugh kills Balor and one legend tells that when Balor was killed, he fell face first into the ground. Then his deadly eye burned a hole into the earth. This hole eventually filled with water and became a lake which is now known as Loch na Súil, or "Lake of the Eye", in County Sligo.

River Maine (Irish: An Mhaing)

The River Maine is in County Kerry (Contae Chiarraí). Its main source is in Tobermaing and has a length of about 26.5 miles (42.6 kilometres). It flows into the Atlantic Ocean at Castlemaine (Irish: Caisleán na Mainge). In ancient tradition it one of three rivers that sprung into life during the reign of Fíachu Labrainne when he was High King of Ireland. In medieval Irish legend he succeeded the previous king, Eochaid Faebar Glas, after killing him in the battle of Carman.

River Nore (Irish: An Fheoir)

The 87 mile (140-kilometre) long River Nore is located in south-east of Ireland. Along with the River Suir (Abhainn na Siúire) and River Barrow (An Bhearú), it is one of the constituent rivers of the group known as the Three Sisters (An Triúr Deirfiúr). Its source is Devil's Bit Mountain (Bearnán Éile) in County Tipperary (Contae Thiobraid Árannand). The mountain, according to local legend, got its name because the devil took a bite out of it. The devil broke his teeth taking this bite and spat out what was to become the Rock of Cashel (Carraig Phádraig). The river winds its way south-eastwards though County Laois and County Kilkenny before joining the River Barrow just north of New Ross. Eventually flowing into the Celtic Sea at Waterford Harbour (Loch Dá Chaoch / Cuan Phort Láirge).

The River Nore passes through some very important historical sites. Including at Durrow (Darú) where the River Erkina (An tOircín) flows and then joins the River Nore to the east. There is archaeological evidence in the area dating to the Bronze Age. An urn-burial found in Moyne Estate dates to about 900–1400 BC. There are a number of ring forts in a land that in pre-history was part of the kingdom of Ossory (Osraige). Home to the Osraige people it was a medieval Gaelic kingdom comprising most of present-day County Kilkenny (Contae Chill Chainnigh) and western County Laois (Contae Laoise).The tribal name Osraige means "people of the deer", and is traditionally thought to come from the name of the ruling dynasty's pre-Christian founder, Óengus Osrithe.

Then there is Ballyragget (Béal Átha Ragad) on the Nore which has older names including 'Tullabarry' (Tualach Bare) the name of an ancient Celtic tribe. To the south of Ballyragget, is Rathbeagh (Rath Beithigh), a hill fort on the River Nore. This fort is said to be is the burial place of Heremon (Éiremhón) of the Milesians. The fort is strategically placed to control an important crossing point on the Nore. There is a legend that Éiremhón and his brother defeated the Tuatha Dé Danann in the Battle of Tailtiu. Tailtiu is the name of a goddess from Irish mythology whose name is linked to Teltown (Tailtinin) a townland in Co. Meath (Contae na Mí), where the battle took place. Legend has it that Eireamhon eventually became the High King of Ireland.

Onwards to Kilkenny (Cill Chainnighis) a the town and surrounding area that has many historic buildings. Prehistoric activity points to settlement in the area in the Mesolithic and Bronze Age. The Kings of Ossory had residence around Cill Chainnigh. On to Bennettsbridge (Droichead Binéid) taking its name from Saint Bennet (c. 2 March 480 – 543 or 547 AD). The first bridge was built here across the Nore in 1285 and dedicated to the saint. The village of Inistioge (Inis Tíog) on the Nore is recorded as a site of battle between the kingdom of Osraighi and an army of Norse in the year AD 962.

The River Shannon (Irish: Abha na Sionainne)

At about 224 miles (360.5 km) the Shannon is the longest river in Ireland. It is said that the Shannon's source is at the Shannon Pot (Lag na Sionna), a pool on the slopes of Cuilcagh (Binn Chuilceachin) a mountain on the border of County Cavan (Contae an Chabháin) and Fermanagh (Fear Manach). It flows to the Shannon Estuary (Inbhear na Sionainne) at Limerick (Luimneach) and into the Atlantic Ocean.

The river, as with some others in Ireland is associated with a goddess. Similar to other such myths the Shannon has a goddess that drowned in its waters. Also in common with others the goddess then merges into the river and becomes the very essence of it and gives it her name. In the case of the Shannon it is the goddess Sionann, linked to the great pre-Christian Celtic pantheon of the Tuatha Dé Danann.

River Shannon (Sionainn) is one of Ireland’s rivers of knowledge said to flow from Connla's Well. This is the the well of wisdom associated with the Celtic Otherworld. The story is very similar to that of the goddess Boann who created the River Boyne after she went to the magical Well to taste the water. Sionann also went to Connla's Well to find wisdom, despite being warned not to approach it. In some sources she is said to have caught and ate the Salmon of Wisdom who swam in the well. However, the well then burst into a torrent, forming the river, then drowning Sionann and carrying her out to sea.

The Sillees River (Irish: Abhainn na Sailchis)

The River Sillees is in south west County Fermanagh (Contae Fhear Manach). Starting at Lough Ahork, it flows through Correl Glen, Derrygonnelly (Doire Ó gConaíle) passes through the countryside of Boho (Botha) going through the loughs of Carran and Ross and ends in Lower Lough Erne (Loch Éirne).

The river was said to have been cursed by St Faber. Saint Faber or St Feadhbar had a pet deer which carried her sacred books. One day the deer was harassed by some hunting hounds and jumped into the Sillees River ruining St Fabers books. The saint then placed a curse on the river making it run backwards. After which the Sillees river, which had once flowed from Boho towards the sea, changed route going instead towards upper Lough Erne. There was a second part of her curse, which was that the river would be good for drowning and bad for fishing. It is reputed that Saint Faber set up a monastery/nunnery in Boho, thought to have been in the 9th century or earlier. There are several sites associated with St Faber around Boho including St Faber's bullán (rock cut basin) and St Faber's well, both found in the townland of Killydrum, Boho. Folklore points to a bullaun (Irish bullán) being of religious or magical significance. With the rainwater collecting in a stone's hollow having healing properties.

River Suir (Irish: Abhainn na Siúire)

The River Suir flows for a distance of 115 miles (185 kilometres). Another of the Three Sisters (An Triúr Deirfiúr) along with the River Barrow, the River Nore which rise in the same mountainous area in County Tipperary, near the Devil's Bit. The River Suir flows through Thurles, Holycross, Cahir, Clonmel and Carrick on Suir, where it becomes tidal before continuing to Waterford and the sea. The area bounded by the Suir and the Barrow formed the ancient Kingdom of Ossory (Osraige). Osraige comprised most of present-day County Kilkenny (Contae Chill Chainnigh) and western County Laois (Contae Laoise). The kingdom was home to the Osraige people, which is thought to have existed from around the first century until the 12 century Norman arrival in Ireland. It was ruled by the Dál Birn ruling dynasty who all claimed to be descended on the paternal line from the second-century king Loegaire Birn Buadach, who was son of Óengus Osrithe, the first king and eponymous ancestor of the Osraige people

The significance of the River Suir, along with other important rivers in Ireland, is highlighted in the sculptures that adorn the Custom House building in Dublin (Baile Átha Cliath). Started in 1781, the Custom House took ten years to complete. Amongst the many sculptures and coats-of-arms on the exterior of the building is a carved series of sculpted keystones symbolising the rivers of Ireland. The riverine heads personifying the Atlantic, and the rivers Bann, Barrow, Blackwater, Boyne, Erne, Foyle, Lagan, Lee, Liffey, Nore, Shannon, Slaney and the Suir

River Swilly (Irish: An tSúileach)

The River Swilly rises near the mountains of Glendore and flows for about 26 miles (41.8 km) through Letterkenny, County Donegal (Leitir Ceanainn, Contae Dhún na nGall) and discharges into the Atlantic Ocean. Its name Súileach is taken from a water monster that was said to have been chopped in half by Saint Columba. Saint Columba (Irish: Colm Cille, 7 December 521 – 9 June 597) was born in Gartan (Gartán) a parish in County Donegal. He was the great-great-grandson of Niall Noígíallach, Irish high king who reigned in the late 4th and early 5 centuries.

Saint Columba, it seems, was no stranger to dealing with river and lake monsters. He is credited with spreading Christianity in Scotland and during this period came across the elusive Loch Ness Monster. He met a group of people burying a man by the River Ness during his journey through the lands of the Picts. Columba was told that the man had been attacked by a “water beast” which had dragged him under the water. In this story Columba sent his follower Luigne moccu Min to swim across the river. When the beast came after him, Columba made the sign of the cross and ordered the beast to leave and the monster fled.

Content type:

- Irish

Language:

- English