Snaefell Mining Disaster 1897, Isle of Man

Snaefell (Manx: Sniaull) is the highest mountain on the Isle of Man (Mannin), at 2,037 feet (621 m) above sea level. To the east the magnificent Laxey Valley sweeps down towards the coastal village of Laxey (Manx: Laksaa) where it meets the Irish Sea. Walking upwards along the track from Laxey, past the tiny settlement of Agneash, a gradual climb takes you alongside the river that flows along the floor of the valley. On a fine day the views are spectacular. As you approach Snaefell you eventually reach the remains of the old Snaefell Mine that lie in the shadow of the mountain. Just above the site nestling behind a group of pine trees there is a beautiful little waterfall. A peaceful and tranquil place to sit and take in the scenery. Nevertheless, there is an air of sadness here, often commented upon even by those without a knowledge of the events that took place at the Snaefell Mine on 10th of May 1897. As if a memory of the tragedy that happened here over a century ago is held within the clasp of the surrounding hills.

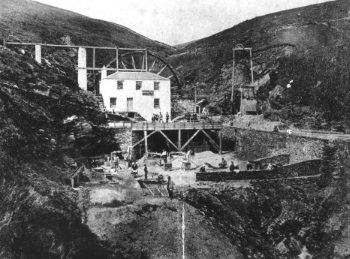

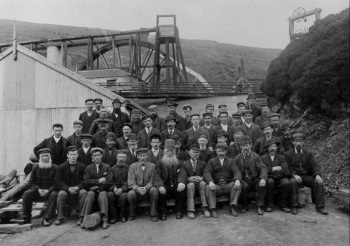

Laxey was the centre of an important lead and zinc-mining industry which was once one of the most important to be worked in the British Isles, and at the time, the world. Lead, zinc, copper and iron had been exploited on the Isle of Man from prehistoric times. Mining remained commercially viable until the early 20th century. Mining, which started at the Snaefell Mine in 1856, was on a much smaller scale than the two biggest Mines on the Island at Laxey and Foxdale. It continued until the mine was finally abandoned in 1909. Disaster struck on the 10th of May 1897 due to an underground fire resulting in the suffocation of nineteen miners and a twentieth, having been rescued dying some days later. The depth of the mine was 171 fathoms (1026 feet). On that sad Monday morning, shortly after 6 a.m., thirty five men descended into the shaft to begin their shift. It was not long before several returned to the surface exhausted and complaining that the stench of gas filled the mine.

This set in motion a desperate rescue attempt with Captain Kewley sending for help from Laxey. He then started a descent into the mine. On the way he met several exhausted, breathless miners struggling to climb up the ladder. As he went further down he discovered others, still alive but unconscious. The rescue attempt continued under hazardous conditions until five in the afternoon when the last survivor, James Kneale, was found, Over the coming hours deeper descents into the mine were made as far as the 100 fathom level with the discovery of bodies. From that point rescue attempts ceased and the awful task of recovery commenced again the next day. Over the next week more bodies were brought to the surface, but due to poisonous gas at the 130 fathom level work had to stop. It was not until the 17th of June 1897 when last body, that of Robert Kelly, was recovered.

At the inquest it was explained that a practice of the miners at the time was to place a nearly burned out candle up against the side of his working place whether it be timbered or not and to light a new candle from it. It was determined that timbers igniting from a candle led to the disaster. It seems that after miners had finished their shift on Saturday 8 May, a candle had been left burning. This then set light to a nearby pit prop leading to a fire in the shaft. Sunday 9 May and the mine was closed, but the fire continued burning as long as oxygen was present. This resulting in carbon monoxide forming which then filled the lower parts of the shaft.

A statue, depicting a Laxey miner, was unveiled in the village in May 2015 to honour those who worked in the village mines. Carved by Ongky Wijanafrom in Carlow Blue limestone sourced from Ireland, it sits on a granite plinth with four Welsh slate panels, They depict the arduous conditions the miners endured. The statue stands in an enclosure of Manx stone, the work of local stone masons Tony Bridson and Howard Kneale. Life was hard for the Manx miners with many having to walk many miles to get to their place of work and then working long hours. In all weathers they would have no choice but to get to the mines. Benefits and health provision were almost non-existent. Self-help was the order of the day with working people combining to form cooperative provision and friendly societies.

Not many would have had the time to sit by the small mountain stream waterfall above the mine. Taking in the beauty and admiring the view down the Laxey Valley toward the Irish Sea. But if you go to this place you will pass the covered mine-shaft where those men met their end on that morning of May 10th 1897. You will see the small plaque that records their names. When you sit by the waterfall think of them and think of the hardships that they had to endure. Remember the struggle that working people have had, to secure the rights that they have today. Remember that there are always those in a position of power, who driven by greed, would be happy to return working people to the lives that were endured by those miners so many years ago.

Those that died:

Joseph Moughtin 28

Louis Kinrade 38

William Christian 26

Walter Christian 21 (brother of the above)

William Kewin 24

John Kewin 29 (brother of the above)]

William Senogles 46

Robert Lewney 24

Edward Kinrade 27

John Oliver 57

John James Oliver 22 (son of the above)

Robert Cannell 41

John Kewley 32

Edward Kewley 22

Robert Kelly 21

Frank Christian 39

Sandy Callan 24

William Callow 29

John Fayle 40

James Henry Corkill 44 (rescued alive but died 26th May)

- Manx

- English