The Manx General Strike 1918

Manx Nationalist Party Mec Vannin have announced that next year - 2018, they will commemorate the centenary of the Manx General Strike which took place in July 1918. The successful strike was a remarkable event in the history of the Isle of Man. It is excellent news and absolutely appropriate that Mec Vannin are giving this the recognition it deserves. As a result we have decided to publish again an article previously written on the Manx General Strike.

In 1918 the Isle of Man was rocked by a General Strike that predated the British General Strike by eight years. It resulted in the annual July 5th Tynwald Day ceremony being postponed. This was a major blow to what is said to be the oldest continuous parliament in the world. The strikers went on to win their demands and this is the story of the events that led to the strike. This important event in the Island’s history was never taught when I was at school, which was symptomatic of the absence of Manx history from the school curriculum and particularly anything relating to organised labour.

Tynwald

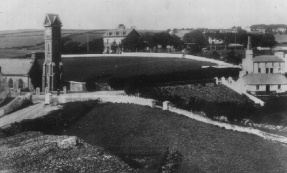

Tynwald is the parliament of the Isle of Man. Every year on 5th July an outdoor ceremony is held at the village of St John’s. It is a legacy of the Viking Norsemen who came to the Isle of Man (Mann) around the year 800AD who ruled for four and a half centuries. A parliamentary system that predates Westminster, Tynwald (Tinvaal in Manx Gaelic) is from the Norse ‘thingvalla’, meaning ‘assembly place’. There are also Norse Thing sites (places of open air assembly) in Iceland and Norway. This is a ceremony that has been continuous for more than a thousand years. The ceremony is held on a four tiered artificial mound and the laws are proclaimed in both Manx and English to the assembled public.

The Branches of Tynwald, the Legislative Council and the House of Keys sit in separate chambers throughout the year. Bills which are passed by both branches and then signed by a majority when sitting together at Tynwald are sent for assent to become law in the Isle of Man.

Working Class Organisation

Manx working class organisation had its roots in the first half of the nineteenth century when the Island was emerging from a largely peasant based economy. The responsibility for the poor, sick and old lay with the family, when these needs were not met it fell to the Church to intervene. As the population grew, from approximately 28,000 in 1792 to about 40,000 in 1821 the towns began to expand. The Church was no longer able to provide the safety net that it had in the past. Forty one friendly societies were formed in the first half of the nineteenth century, the first being founded in 1790. They helped to augment the role that had previously been undertaken by the church.

A significant development in the growth of friendly societies and cooperatives was the expansion of the mining industry. The most successful being the lead mines at Foxdale and Laxey. Foxdale mines were once the richest in the British Isles. In 1821 they produced 6,868 tons of lead ore; in 1875 11,898 tons of zinc blend; in 1877 186,019 ounces of silver, and in 1891 the produce of the Foxdale mine was valued at £45,200. Miners were to play a significant part in the development of working class organisation on the island.

The first recorded attempt to form a trade union was in 1821, an attempt to stop its formation was defeated at a trial in Castle Rushen in June of that year. However, the most famous attempt at forming an early trade union was not directly concerned with Manx workers. The Isle of Man being seen as a neutral venue was chosen as the place to launch the Operative Spinners Union of England, Ireland and Scotland in 1829. The meeting organised by Donegal man John Doherty (1798-1854) was held over three days in Ramsey in December 1829 resulted in the following motion being passed ‘that one grand union of all operative spinners, in the United Kingdom now be formed, for the mutual support and protection of all’.

At the turn of the twentieth century there were attempts to organise various sections of the Manx Working Class including agricultural workers. In 1917 efforts were made to organise a union for general workers in the Isle of Man. There was considerable support for this against a background of cost of living rises of 78% since 1914 and no defined maximum working week. The first branch of the union was formed in Douglas. One of the first actions of the newly formed union secured a fixed working week of 56 hours. This early success of the Douglas Workers Union led to the formation of other branches in Ramsey, Castletown, Rushen, Laxey and Peel. The rail workers throughout the Island achieved notable success in gaining wage increases. These early successes brought other sections of workers into Union membership. As well as the predominantly male employing industries great efforts were also made to organise female workers and a Workers Union set up a branch for women members in Douglas. This increase in Union activity toward the end of the First World War formed part of the background to the 1918 General Strike.

Campaign for Direct Taxation

The events which lead up to the strike had their basis in the campaign for direct taxation and a Manx reform movement had been campaigning for the imposition of an income tax on the Island. The original campaign had been fought in order to secure old age pensions. Set against the calls for reform was the then Governor Lord Raglan, who had been Governor since 1902. It was his opposition to reform that made him unpopular with ordinary Manx people. At the Tynwald ceremony in 1916 he had been confronted by a demonstration. The demonstrators held placards and greeted the governor with shouts that he resign, implement old age pensions and direct taxation. At one point he was struck by a grass sod thrown from the crowd.

This campaign for a pension was temporarily diverted into a fight to get the Manx Government to grant Manx bakers a flour subsidy similar to that given to English bakers to enable a reduction in the price of bread from one shilling to nine pence. These calls for parity with United Kingdom bread prices were ignored. This resulted in protest meetings being held throughout the Island and led to Tynwald meeting to discuss the matter. A committee of enquiry was appointed which resulted in a six month subsidy from November 26th 1917 to keep bread prices at 9 pence a loaf.

The agreed subsidy was to last seven months until Friday June 28th 1918 the Governor in his annual financial statement to Tynwald announced the termination of the subsidy at the end of the month. At the instigation of the Isle of Man Workers Union representatives of the various trade unions on the Island were summoned to a meeting in Douglas on June 29th. At this meeting it was decided that unless the nine penny loaf remained a general strike would be called. There followed Island wide meetings to enlist public support and demands for the passing of an Income Tax Bill. With the cessation of the flour subsidy notice was given by the bakers that from July 1st 1918 the price of the loaf should be increased to one shilling. The Governor then decreed that the price should be fixed at ten and half pence. This left a situation where bakers threatened to close down their bakeries because they said they could not produce bread at that price. The workers stated that they would not accept any price over nine pence as was being paid by English workers.

The General Strike

This set in motion a series of events leading to the Manx general strike. A meeting was held attended by the various unions where the campaign strategy was drawn up. A strike committee was set up with representatives of the National Union of Seamen, Typographical Association, Shop Assistants Union and the Workers Union. A thousand strong meeting was held outside of the Government Office in Douglas to announce the strike with word being sent to other parts of the Island. The strike commenced on July 3rd 1918 and resulted in a stoppage of work throughout the Island. The strike was undertaken with some skill and a high degree of organisation. Situations that arose over the duration of the action appear to have been dealt with by the strikers quite skilfully. Clearly the use of picketing and direct action was a key to the ultimate success of the strike. The daily steamer from England to the Isle of Man was allowed to sail on the understanding that a return passage would not be allowed. The cargo workers in Douglas ceased work, the schools closed and tram and rail services were halted, shops, offices and factories were shut.

A number of incidents arose during the action. A coal yard that attempted to stay open was invaded by a crowd and closed. A minimum amount of work was agreed to be undertaken in the gas works to maintain supplies and when a clerk attempted to do more than was necessary he was escorted home by a jeering crowd. A member of office staff who attempted to drive a tram car was chased away from the depot. A crowd prevented a train from leaving a station by raking out the fires from under the boiler of the engine. Fishing boats were allowed to land their catch but sold the fish at a price fixed by the strike committee to the people. The strike committee also allowed shops in poorer quarters to open between 7am-9am to enable the purchase of food. It seems clear that the strike committee had put itself in a very commanding position in regard to the control of trade and industry.

The Government had been taken by surprise by the strength of the action and was put into a position of making requests to the strike committee. A request that came to the committee was for permission for the members of Tynwald to be allowed to travel to the annual Tynwald ceremony. However, the Governor fearing the possibility of disorder and demonstrations at the ceremony postponed it and for the first time in living memory Tynwald did not take place on July 5th 1918. Stranded tourists to the Island approached the Governor for help to get off the Island, who referred them to the strike committee. The committee refused and the visitors went back to the Governor to ask if a warship could be sent to take them home. This was not done. The Governor had also complied with the strike committee’s requests to keep in camp all military forces on duty on the Island at the time. These were mainly engaged in guarding the wartime alien camps that existed at that time.

On the second day of the strike the Governor asked to see the Strike Committee and he offered a ten and a half pence loaf but this was refused. The Governor then called a meeting of the Legislative Council. Following this a notice was posted outside of all Government buildings:

Arrangements have been made for the immediate restoration of the ninepenny loaf. The Lieutenant Governor trusts that business will be resumed as early as possible and that no person shall be victimised for participating in the strike.

The Strike Committee called a meeting of some 2000 people and the workers were thanked and asked to return to work. This news was transmitted by telephone and telegram to all parts of the Island.

Conclusion - After the Strike

The strike took place from Wednesday July 3rd 1918 to Friday July 5th 1918. The aim of the strike was to enable the imposition of a bread subsidy. However, the roots of the strike go back to a long and protracted campaign for old age pensions. Although a previous pensions bill was carried through the House of Keys it failed to get through the Legislative Council. It was the success of the 1918 strike which led to the imposition of an income tax to initially pay for a bread subsidy that later resulted in the introduction of pensions on the Island.

The strike itself was a unique event in the Isle of Man and although successful had negative results for some of those involved. Attempts at victimisation took place. A prominent director of several local companies called for the Chairman of the strike committee to be sacked from his job on the Isle of Man Times. The threat being that orders from the firms with which the director was associated would be withdrawn. However, the editor at the time refused. Others did suffer, including two prominent leaders of the strike who lost their jobs and had to seek work off the Island. A renewed stoppage suggested to protect them was prevented at the request of the two men.

A further result of the strike was the strengthening of trade unions and political labour representation. The Manx Cooperative Society was also formed. Lord Raglan handed in his resignation at a meeting of the Tynwald Court on 17th December 1918 citing ill health as the major reason.

Sources

‘Diocesan Histories, Sodor and Man’ SPCK 1893 A.W. Moore

‘History of the Isle of Man’ Volume 1, 1900, A.W. Moore

‘Industrial Archaeology of the Isle of Man’ 1993 (amended 2006) Manx National Heritage.

‘The Manx Quarterly’ Number 20 April 1919 (Manx Museum, Library & Archive Service)

‘Delegate Meeting of Operative Spinners’ Ramsey 1829 (Manx Museum, Library & Archive Service)

‘Reminiscences of the Manx Labour Party’ Alfred J Teare, October, 1962 (Manx Museum, Library & Archive Services)

‘Mona’s Herald’ June 23, 1829 (Manx Museum, Library & Archive Services)

‘Mona’s Herald’ March 30, 1921 (Manx Museum, Library & Archive Services)

‘Isle of Man Weekly Times’ September 23, 1955 (Manx Museum, Library & Archive Services)

‘Manx Labour Party Review’ December 1960

‘Manks Advertiser’ 1812, 1811, 1814

‘Workers Union 1898-1929’ Richard Hymans 1971.

‘Manx Memories and Movements’ Samuel Morris MHK

- Manx

- English

- Log in to post comments