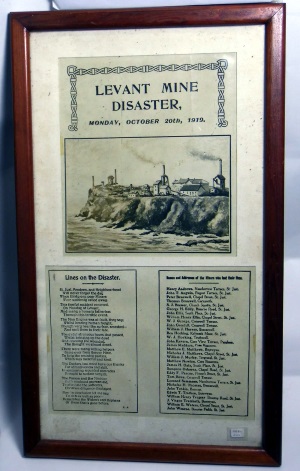

Levant Mine Disaster, Cornwall 20th October 1919

A member of 'Kernow Matters To Us' (KMTU) lost two ancestors in the Levant disaster. Their wives were evicted within a couple of weeks being unable to pay the Bolitho Bank of Cornwall the rent for their cottages and ended up in the Penzance Union Workhouse.

Here's the background to that fateful day:

The cliffs of St Just provide a dramatic backdrop the for the scene of one of Cornwall's worst mining disasters in recorded history.

Perched on the edge of the cliffs remain several buildings which offer insight into the work of the men and women who risked their lives at Levant Mine; commonly known as 'Queen of Cornwall's submarine mines'.

Hidden beneath the sea is a labyrinth of tunnels which stretch a mile out, once used to extract tin and copper from the earth.

The mine was operational between 1820 and 1930 and produced 130,000 tonnes of copper, 24,000 tonnes of tin and around 4,000 tonnes of arsenic. The earliest records of copper being mined at the site date back to 1670. It was a lucrative business, with some £2.25 million returned.

The miners would descend 700 yards below the ocean, where the temperature would reach 30 degrees, and one false strike with their picks could mean the end. The notorious '40 Backs' tunnel was a mere 40 feet from the seafloor, and in rough weather, miners could hear the rocks being thrown about just above their heads, with the roar of the waves serving a reminder of the perils they faced.

To aid the miners in the vast network of tunnels, pit ponies were used – the only mine in Cornwall where they are said to have been so

It was a dangerous job, having to navigate the winding paths among the precarious and steep cliffs.

An inquest reported by the Royal Cornwall Gazette, dated September 5, 1845, told of a young boy, called William Grenfell, around 9 years of age, who died on what was said to be his second day of employment at the mine.

He had been playing with another young lad, Frazier.

The report said:

He fell 25 fathoms, or thereabouts, and received such injuries that he died shortly after.

The miners also faced the constant risk of being killed or injured as a result of falling equipment or earth. A Mr John Rowe died instantly while down the mine on September 15, 1840, by an 'immense mass of ground falling on him, which crushed him almost flat'.

The newspaper also reported how the accident occurred in the presence of his comrade and brother.

Evidence suggests this area of the coast was mined for thousands of years, as far back as the Bronze Age, some 3,500 years ago.

Now owned by the National Trust, the site is home to the only Cornish beam engine anywhere in the world that is still in steam on its original mine site.

In the mid-19th century it became an attraction for tourists, with some attempting submarinal descents.

The advancement in the technology allowed the workers to head deeper and deeper in the pursuit of the metal hidden below the ground.

It was the big accident of 1919 which led to the demise of the mine. On October 20, the man engine, which transported the miners underground, failed.

The rod which controlled the movement broke. The men on the device plummeted down the 1,596-foot shaft, with 31 killed.

Those aboveground at the time of the accident could only wait to hear about the fate of their colleagues, and once the news hit the towns and villages, wives and mothers flocked to the site in a desperate bid to find out about their loved ones.

A graphic description of the accident, and its terrible consequences was supplied by Robert Penaluna, a young St Just miner who was on the man-engine at the time.

I was coming up on the man engine' he said 'three steps below the 150 fathom level. The engine was full of men. We had travelled up part of the way between one sollor and another when the engine dropped a little but then picked herself up again. Then she fell away to the bottom. I was thrown on my chest upon the sollor. My chum on the next sollor below (Charlie Freestone, aged 25, of St Just) had his feet caught between the step on which he stood and the sollor, and was swung upside down. I was not hurt except that a piece of timber struck me on the leg. For about three hours I was down there before I could come up. Then I walked up the ladder through the pumping engine shaft, to the surface. Before that I picked up Freestone, who was suffering from shock, and dragged him through a manhole on to the sollor upon which I was standing. He fainted in my arms. We got him back to the 150-level shaft and men of the afternoon shift helped to drag Freestone to the surface with ropes. When the engine broke it was a tremendous crash for in dropping she knocked away timber and everything else in her path. The engine rod on which we were travelling shook violently. The smash gave a terrible shook to us all, and everybody lost heart and nerve entirely. I wouldn't go through an experience like that again for the world.

Although the mine continued to operate for another 11 years after the incident, it never truly recovered, and the reality of the dangers facing those employed at the mine became all too evident, and the mine closed in 1930.'

The Levant Poem was written by an unknown person known only as K.A. and appeared in the local newspaper as part of an appeal for funds for those left behind.

St Just, Pendeen and neighbourhood will never forget the day,

When thirty-one poor miners were suddenly called away;

This fearful accident occurred, on Monday at Levant,

And many a home is fatherless through this terrible event;

The Man Engine was at fault, they say: while bearing human freight,

Though very near the surface smashed - and sent them to their fate;

The awful strenuous hours that passed, whilst bringing up the dead,

And rescuing the wounded, the thought we almost dread;

There were many willing helpers came over from Geevor Mine,

To help the rescuing parties, which was merciful and kind;

The doctors, too deserve our thanks for attentiveness and skill,

In succouring wounded comrades brought to surface very ill;

The Parson and the Minister both rendered yeoman aid,

To alleviate the sufferers, Christian diligence displayed;

Now in conclusion let me say to rich as well as poor

Remember the widows and orphans of those that's gone before

Anon – signed only ‘K.A.’

- Cornish

- English

- Log in to post comments